I am slow thinker. I enjoy thinking – but slowly - marinating as the various thoughts blend with my life experiences until they finally coalesce into a clear view or decision in which I have confidence.

If pushed I am happy to say “I don’t think in public”. On the odd occasion that I have been in a formal debate and my opponent has made an interesting comment my reaction has generally been to say: “Wow, that’s interesting – let me think about it and get back to you”. Rather than a quick repartee that would enhance sharp debate, I would much rather find a small area of common ground and work out from there until we find a small area of disagreement on which we can chew until we find further common ground. That approach has led me into many conversations with people around the world, who may or may not share my approach to life, and to many situations that have varied from the hilarious through the moving to the scary. You will find some of them in the stories that follow.

It was in 1994, more than 25 years after I had first arrived in Africa, that I finally visited a game park. Fiona and I were working on a project in Tanzania, at the end of which she persuaded me to visit the Ngorogoro Crater. We travelled by train from Dar to Arusha, along the Chinese-built Tan-Zam railway. Like the trains on which I had travelled in rural China some years earlier, they seemed designed to travel at the same speed as the mosquito. Unlike those in China, they did not have a man with a wok and a gas cylinder at the end of each carriage cooking noodles for the passengers. In Arusha we stayed overnight at a small hotel before setting off next morning into the crater, sitting on the bench seat at the back of a Land Rover with the option to pop our heads through the open roof to observe the animals. Whenever our driver/guide saw something of interest he would stop for us to take a look and/or a photo.

Although the scenery was spectacular - open grasslands dotted with instantly recognisable Acacia trees – this was what I was accustomed to after 25 years of working in rural Africa. It was not long before I asked if we could climb to the top of the crater and take a look down. As we arrived at the top I began to hear a roar – a roar that I thought I recognised. I waited on tenterhooks in anticipation as the sound increased in intensity. And then it suddenly appeared round the corner and I shouted out: “Yes, it’s a 1960 Leyland truck”.

To me the thrilling sound of that straining diesel engine climbing in the thin air represented the work-horses, the trucks and buses and the small tractors and standing engines (those that de-husked rice, ground maize or pumped water from wells) which – in the days before electronics - were infinitely repairable and underwrote so much of the economic activity in the countries in which I had been working. Travelling to me had always been functional, a necessary process of getting from a to b to allow me and others to do whatever was our current focus in the hope of contributing something useful to the communities with which we were working.

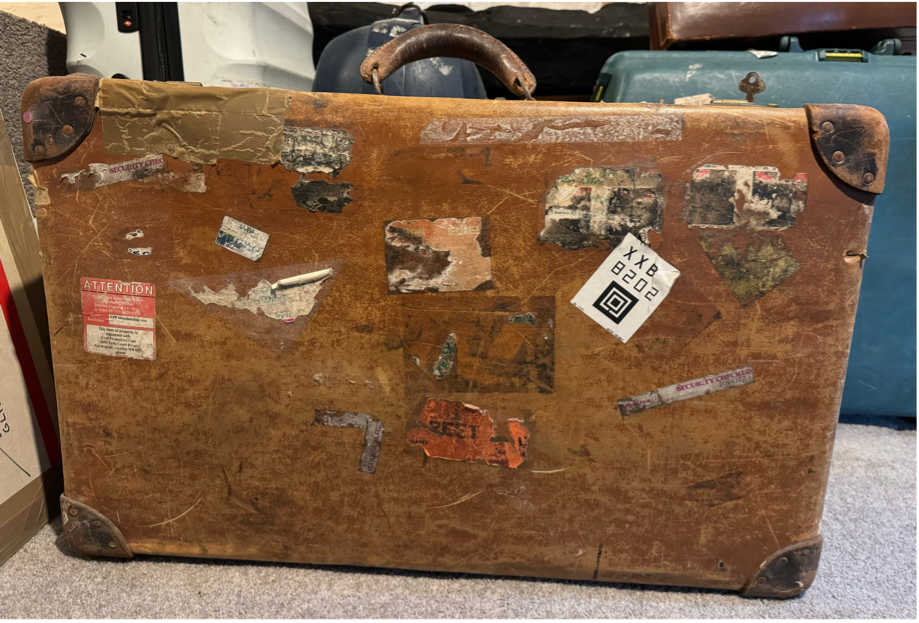

Hence I have never thought of myself as “a traveller”. That I have travelled is not in doubt. During the 30 years from 1973 to 2003 I kept a record of every flight that I took. Looking back I see that during those 30 years I flew some 2.46 million miles, on 1,025 flights on 67 different airlines involving some 58 countries and 138 different airports. It was a flight every 10 days for 30 years. At the time we had no idea about climate change…. and in an era before the web, mobile phones, Zoom and What’s App hopping on a plane so that we could bump through the bush in a Land Rover or Land Cruiser or Toyota Hilux was simply the functional mechanism that allowed me to do my work.

In those days the Boeing 707 and the Douglas DC8 were the world’s flying workhorses – with a single aisle, on each side of which were three seats (window, middle and aisle). As one walked down the aisle to the toilet or for an extra bag of crisps you would see everyone who was on the plane in the 40 or so rows of seats - and they could see you. I am sure I am not alone in looking at these faces and wondering why they were travelling to Kinshasa or La Paz or Mindanao. These were not places generally frequented by tourists so most would be going there for a purpose and it was a fascinating challenge to guess what that was. Whilst those in uniform (nuns, priests, the military) were self-evident the others could include aid-workers, teachers, students, businessmen, diplomats, engineers, spouses and wheeler-dealers – many of whom I might encounter not only in the immigration queue at arrivals but also during my travels in the country concerned.

You will meet some of them in the travels that follow…

DIPLOMACY ON A RICE BARGE AND OTHER DIPLOMATIC ENCOUNTERS

VENEZUELA. It’s 1976 and I am on my way to Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia. Arriving early morning in Caracas for an overnight stay, my first port of call was the British Embassy.

OFF TO AFRICA

Some nine years after deciding that I wanted to work in agriculture in what was then termed “the developing world”, in the early summer of 1968, I found myself both completing my doctoral thesis at Wye College and preparing to travel to Africa

SOUTHERN AFRICAN JOURNEY 1968

Having arrived at the College in September 1968 with not even a smattering of knowledge about farming in the sub-tropics, somehow during that first term I managed to engage with the students and keep them interested.

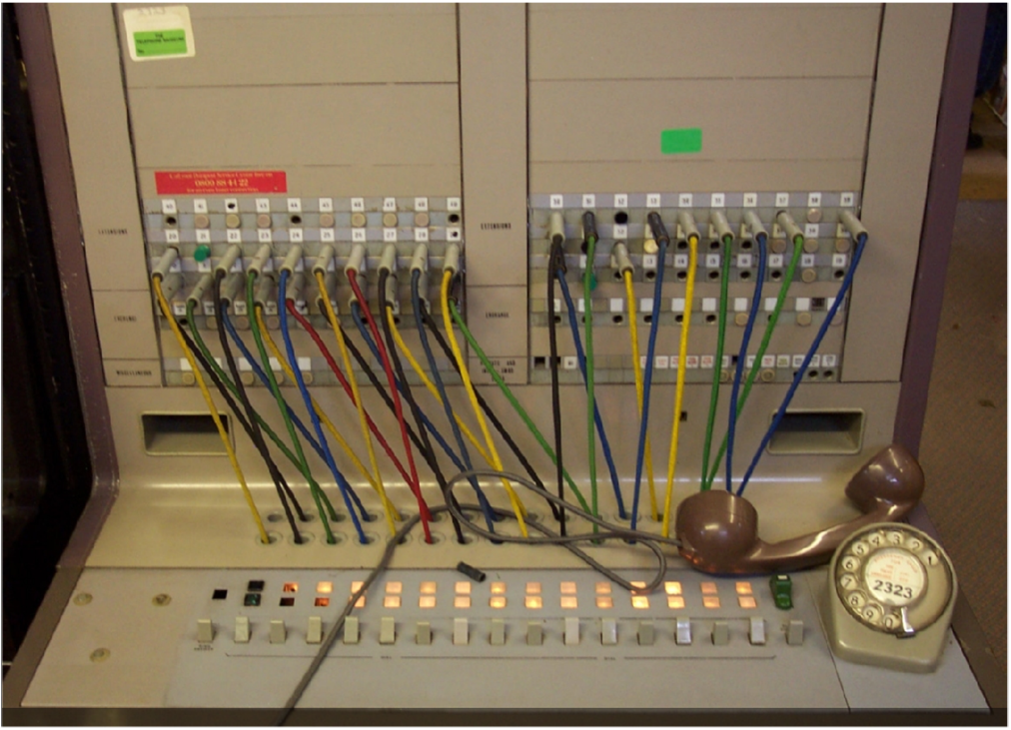

THE TELEPHONE EXCHANGE

It is September 1968 and I had just arrived in Swaziland to start my first job as lecturer in crop production at the Swaziland Agricultural College and University Centre (SACUC).