THE TELEPHONE EXCHANGE

It is September 1968 and I had just arrived in Swaziland to start my first job as lecturer in crop production at the Swaziland Agricultural College and University Centre (SACUC). As I entered for the first time the foyer of the college, I noticed on the left-hand side the reception area. It was made of timber, extended for about four metres and stood around chest high. Behind it sat the receptionist and alongside her sat the telephone switchboard.

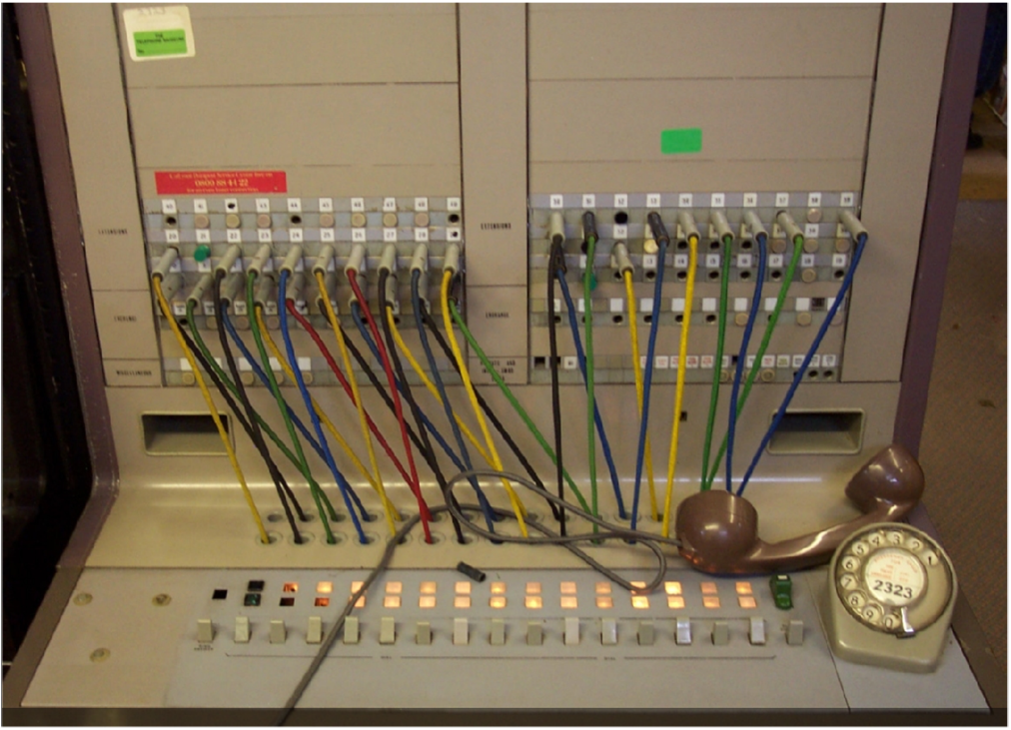

There was only one external phone line coming into the college which was connected through the switchboard to a series of internal lines that allowed an external call to be connected to the offices and workshops located throughout the college. This was done by placing the plug at the end of the incoming wire into the appropriate socket on the exchange. If the intended recipient of the incoming call was not at his/her desk then the wire could be plugged into other sockets to check their whereabouts. For outgoing calls the process was reversed, with a request made from someone in an office to the switchboard through which the requested external number would be dialled. If the external line was busy - as was often the case - then a request for an external call would be put in a queue.

In charge of these acoustic comings and goings was Beauty Magagula – who did a great job. But if Beauty was out of sorts or had been upset by someone then an incoming caller might be told that there was no reply to that extension or the search for them around the campus might be cursory rather than thorough. Alternatively, a request for an external call might find itself routinely relegated to the back of the queue. Perhaps not surprisingly, we all walked on tiptoe around Beauty and kept her happy.

MORE ABOUT THE PHONES AT SACUC

Alan and Mary Catterick, colleagues at SACUC, kindly reminded me of the following details about the phone system……The single telephone line was connected to the local phone exchange at Malkerns – 4 miles away. When the college was operational this single line connected the Malkerns Exchange to ALL the phones on the campus in the form of a party line. During normal working hours all calls came into or from the SACUC reception c/o Miss Magagula who would then transfer incoming calls to whoever the call was for. Out of working hours the SACUC line was connected to all the house phones. There were no individual phone numbers and incoming calls out of hours rang in ALL the connected houses – although the Malkerns exchange operator may have allocated several rings for each of the connected houses. In theory anyone could listen in to the phone calls but this was in practice a very rare occurrence. Outgoing calls had to be pre-booked with the Malkerns exchange and for overseas calls you had to wait for, in some cases, two or three days. The cost of all calls from SACUC was debited by the Swaziland Post office to the SACUC account and the Bursar (Mr Dlamini) would request payment from the individual officer for any personal calls. As can be seen in the letterhead, in addition to its single landline, messages could be received by telegram (Sacuc: Mbabane) whilst any post would be collected daily from a “box” at the local post office some four miles away.

The power of the telephone operator reminded me of living in Bangkok some 15 years later, where traffic was often grid locked. There were several major, spine roads radiating out of Bangkok - off which ran many short residential streets (known as a Soi) on both sides. Out of (and into) these came the householders wanting to join or to leave the main road, access to which was controlled by a policeman who wore white gloves and who, with artistic gestures, co-ordinated the traffic flow by radio with his peers. It was usually the same policeman on duty each day and he had absolute power over who left or entered the Soi and when. On the occasional festival day he would be seen standing on his little rostrum at the road junction surrounded by boxes and boxes of presents, beautifully packed, which had been given to him by the individuals living in the street who were seeking to ensure recognition and priority when they arrived at the junction.

In February 1973, when I was in deep rural Zaire, my diary reads “Mr Maloba told me that it would now not be possible to visit Goma - partly because he had not completed his business and partly because with a subsequent tight schedule he could not guarantee that his Air Zaire flight would arrived on time to connect with the internal flight. I tried to ring the office in London to discuss this but all lines were fully booked. An enthusiastic operator woke me at 0130 in the morning to say that he was about to try again – but I declined the opportunity as I thought it unlikely that anyone would be working in the office in London at that time!”

The saga of telephone calls made (or not made) and of telegrams which did not arrive confirmed in my mind that access to a telex machine was absolutely essential for work overseas.

A telex machine allows a typed message to be converted to a low-bit-rate electrical signal, which is transmitted over the network—usually through telephone lines – to a remote telex machine. A message is first printed onto a punched tape which is then run through a tape-reading device. The machine at the other end prints out the same punched tape which is then passed through a punched tape reader and printed out. The process was a little cumbersome but absolutely secure and pretty reliable. Over time it was replaced by the fax machine and in turn by digital transmission over the web.

When I first travelled out to Africa in 1968, to Uganda and Kenya and then on to Swaziland, all the arrangements were made by airmail letter and all payments were made in cash or in travellers’ cheques. The possibility of phoning did not come into one’s mind. During those four years in Swaziland I spoke to my parents just once a year - on Christmas Day, for just ten minutes and at an exorbitant cost. The time of the call was pre-booked well in advance through the operator and my parents would have been notified of the time of the call by my sending them an airmail letter. We would each speak for five minutes knowing that the operator would cut us off after ten minutes on the dot.

In December 1975 I found myself working in South America where my itinerary included Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and Venezuela. I have recently found a letter to my parents dated 17th December 1975 and posted the same day in Caracas. In it I expressed confidence that – despite the pressures of the Christmas post - they would receive the letter in England before Christmas Day (just 7 days later). We had an absolute - and justified - faith in the postal system.

I was in Kinshasa on evening in February 1973 in what was then called Zaire (a former Belgian colony). I was on my way to Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic (before President Bokassa declared himself Emperor and it became the Central African Empire). I had a colleague in Brazzaville, the capital of The Congo (formerly a French colony), to whom I needed to speak to synchronise our travel arrangements. Brazzaville lay on the opposite side of the Congo River. Kinshasa and Brazzaville are the world’s two closest capital cities – just a few miles apart - and at night the lights of Brazzaville were clearly visible across the river.

I was in my room in a hotel with a view across to Brazzaville when I decided to make the call. I lifted the receiver and dialled zero for the hotel operator and asked her for the number in Brazzaville. She then dialled the central exchange in Kinshasa and repeated the request - linking the wire from my room into the plug to the central exchange. The operator in the central exchange repeated the request to an operator in Brussels who then repeated the request to an operator in Paris who then repeated the request to the central exchange in Brazzaville who then repeated the request to the operator manning the switchboard in the hotel in which my colleague was staying. Finally, the operator in the Brazzaville hotel plugged the wire into the socket for the room of my colleague, who fortunately happened to be in his room, and we were connected. This was possible thanks to each operator requesting the right number (done verbally) of the next operator in the chain and then plugging and retaining the relevant wire in the relevant socket during the time that the call was being requested and in progress – AND the intended recipient being in their hotel room. A call to someone whom I could effectively see five miles across the river required the involvement of six switchboard operators in two African and two European capitals - a round journey of nearly 19,000 km!

During the 1970s I went to Bolivia several times – always flying first to La Paz before travelling to other parts of the country. We landed at El Alto Airport – aptly named as it is 4,062metres above sea level, or roughly half the height of Mount Everest, and the average temperature is 6’C. As one left the air-conditioned fuselage of the plane, crossed the tarmac and queued out in the open at the shack which served as passport control, one was immediately struck not only by the biting wind but by the struggle for breath – there being roughly half the level of oxygen as at sea level. One was again aware of the thin air when taking off as the runway is 4,000 metres long (4 kilometres or 2.5 miles) to allow the plane to attain lift. Until one was used to the experience, rushing down the runway for the first three kilometres and looking out of the window with the wheels still firmly fixed to the ground was quite scary. You found yourself lifting your feet off the floor in a vain attempt to get it into the air – which it eventually it did with a snail-like increase in altitude.

Driving down the windy road into La Paz (at a mere 3,640 metres) one saw the local people walking around as if at sea level – with their large chests to increase the volume of air taken in and their red faces rich in haemoglobin to extract the available oxygen. Booking into a hotel – head still banging – one would press the button in the lift for the appropriate floor and then notice another button marked OXYGEN. Once in the room, and before lying down to rest, in addition to the nine numbers on the phone’s rotary dial there was an additional one called OXYGEN. This was a sop to those of us unused to this altitude. If dialled, someone would be with you in no time together with a canister of oxygen.

In 1974 the small consulting company that I was working for decided to establish an office outside of London – looking for somewhere with a station nearby that could get us back into “town” within 90 minutes. We ended up with a shortlist of three towns - Alton in Hampshire, and Abingdon and Thame - both in Oxfordshire. What attracted us in all three cases was that all of them were slated to be connected to what was called Subscriber Trunk Dialling (STD). Until the arrival of STD it was possible to direct dial another person only if they lived within the area of your local exchange area. To make what was called a “trunk” call one had to phone the operator in your local exchange and request the call - holding on whilst they dialled the number.

During 1993-9 I was responsible for a large enterprise development project in Ghana, funded by DFID. One of several people who made the job easier was Leslie Tribbeck, then retired but who had lived in Ghana since the 1950s working for Unilever’s United Africa Company (UAC). He had come out as a young man and risen to be its Finance Director. Now retired, he was not only a highly experienced accountant but also had a love of Ghana and an encyclopaedic knowledge of the country and how it worked. He once regaled to me how his wife Audrey had phoned him in the office late morning on a Saturday to ask if he could call in and get some bread and other foods from the UAC store. Conscious that he would struggle to get there before closing time he phoned to place an order that he could pick up from the security guard. He dialled the operator – a prerequisite in those days before direct dialling – and asked for the UAC store. He was surprised to be put through to Ghana Railways. He tried again and the same thing happened. So when he dialled the operator for the third time he asked why he had been put through to Ghana Railways – to which she replied: “I have just been on a course to encourage me to use my initiative. So as the UAC phone was busy I decided to give you the next available number!”.

I first arrived in Trinidad in December 1975 on my way through from Bolivia to New York and Washington and returned for a second, longer visit in April 1976. It was, at the time, a small country rife with political factions – with groups representing people of European, African and Indian descent and the various trade unions. Eric Williams had been the prime minister for some time and the economy was struggling. Amongst other things the telephone exchanges were completely overloaded and to make a phone call one had to wait for up to 20 minutes simply to get a dialling tone. Once the dialling tone burst into life, and one had absorbed the joy of hearing it, one could dial the required number. On one occasion, having secured a dialling tone I dialled the number for Barclays Bank where I wanted to make a transfer overseas. When the phone was answered a lady told me that this was a private number and sorry it was not Barclays Bank. Over the next half hour, having checked that the number I was dialling was correct, the exercise was repeated with the same result – the lady told me that it was a private number. Repeating the exercise for a third time, when the lady heard my voice she simply said “Darling, why don’t you come over for a drink?”. If I had, I suspect that my life might have taken a very different course.

Before the age of the mobile phone (which began in earnest around 1995) we communicated through the “landline”- which was accessible either in the home or office or in a public phone box into which coins were inserted - and we also relied upon an efficient and effective postal service. I remember when working in rural India in 2012 I was sitting with a group of Indian colleagues discussing the project when one of them said “Ah – the penny’s just dropped”. Perhaps not surprisingly they did not know the origin of the phrase and so I recounted how, as a small boy, when travelling in our ancient car my father would routinely stop and require us all to get out and use the public toilet. When a cubicle was needed this required a penny being put into the slot before the door would open. Occasionally, the penny was inserted but the door did not open. Hence the tangible sigh of relief when “the penny dropped” and the mechanism opened the door. On hearing this explanation in this digital age my Indian colleagues reacted with a mixture of giggles and disbelief.

I started learning to play the clarinet around 1954 and I used to purchase my reeds from Boosey and Hawkes. The reeds came in a simple, cardboard case in which was written the telephone number for their shop in London – which was Langham 2060 or Gerard 1648. To phone the former number one would need to dial 0 for the operator at your local telephone exchange, ask for Langham 2060, wait until she got through to the other end, put the money into the coin box and then start speaking until the pips rang to say that your time was up unless you put in more coins.

Sometime around 1994 I was due to travel to Johannesburg on a flight leaving Heathrow at around 6.30 pm. Conscious that I was a ditherer when preparing to leave – always checking that I had my tickets and passport – I determined to “relax” and not worry. Before leaving I took a bath and without checking anything – and proud of myself for so doing – around 2.30pm I climbed into the taxi for the two-hour journey to the airport. After about an hour I succumbed to that urge to check the top pocket in my shirt to find nothing there – no ticket and no passport. Panic. The first public telephone that we could find on the M4 was at Newbury Services – where I got out of the taxi and ran in to find a public phone booth, dialled home, put in the coins (which fortunately I had with me) to learn that the ticket and passport were both sitting on the bannisters at the top of the stairs. Aware that I had left them behind, there was nothing Fiona could do to contact me but simply wait until I had realised and called her. I put the phone down and rang British Airways at Heathrow – with yet more coins – and, perhaps because I was a frequent traveller with them, I was told that there was a second flight to South Africa at 2000 and although it was to Cape Town they would happily change the booking. I agreed and went out to my taxi driver to ask if he could radio his operator to get another taxi to pick up the documents from our house and bring them to Heathrow. I then rang Fiona to update her and got back into the taxi to proceed to Heathrow – fingers crossed. Keeping in touch using their radios the two taxis made a rendezvous and the documents exchanged hands. I made the flight to Cape Town and the connection to Johannesburg.

Whilst on the flight to Johannesburg I was reading a book on farming when the gentleman sitting on the opposite side of the aisle engaged me in conversation and asked me about the book. We chatted. As the flight came in to land he asked me if I needed a lift from the airport into town. I explained that a colleague was meeting me whom I had not met before and so thanks but no thanks. We exchanged business cards. His card read Cyril Ramaphosa – then a high-profile businessman and very close to recently-elected Nelson Mandela. Despite not taking up his offer of a lift, we continued a dialogue by email for some time until events took him to a higher level – eventually to be elected President of South Africa - and our correspondence tapered off.

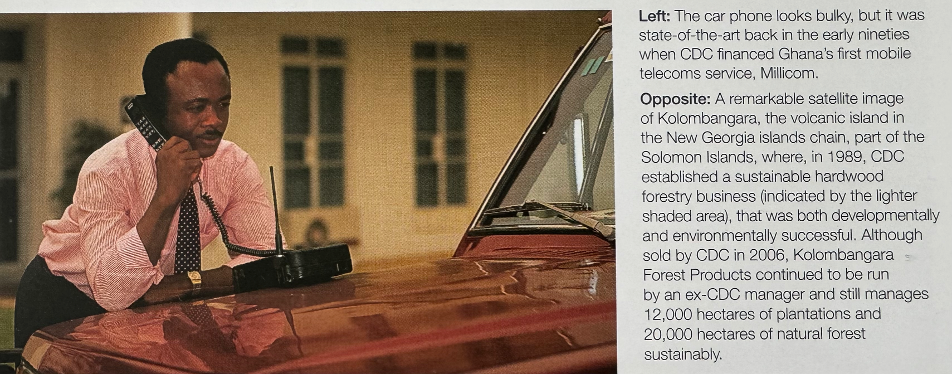

It is hard today, when everything is instant, to imagine the need for coins, switchboards, operators, booking international calls days in advance, telegrams and airletters. But back then it was the norm. As you can see above, this bulky “mobile” phone was state of the art in the early 1990s when CDC invested in the Ghana Venture Capital Company (which had been promoted by our little company Rural Investment Overseas Ltd – RIO) which in turn had invested in the first mobile telecoms service in Ghana.

Because we did not know any different life went on, we planned ahead, forests were planted, there was more time for discussion, people were innovative and cared for each other – and we always ensured that we had a few coins in our pockets.