THE JOY OF LESSONS LEARNED

Over the decades, I have found both fun and joy from the process of harvesting, learning and sharing the lessons of experience, and I have been thinking about why that might be.

After all, the word lesson has overtones of formality (like a music or a biology lesson) or of sanction (that will teach you a lesson!). The OED gives six definitions for the word, most of which reflect this sense of formality or sanction, but part of one of them reads: an occurrence from which instruction may be gained – and that is the meaning reflected here…….whilst “learn” is defined as “To acquire knowledge……..as a result of study, experience or instruction…develop an ability (to do something)”.

We are all learning all the time, some of which is reflected in our reflex actions. But much is lost either through overload or through the next experience bounding over the horizon, or simply through shortage of memory capacity. In my case, it is exacerbated by being a slow thinker, reflected in my general unwillingness to “think in public” and the need always to prepare for events. But the value of such lessons need not be limited to oneself. They can also be shared with others and/or help to build an institutional memory.

The need to think this way became essential when I started working in the rural sector in Africa and Asia, in which I was charged with addressing particular issues with a view to finding/recommending a way forward. The nature of those issues varied greatly, as did the physical, ecological, social and political environment within which they occurred. As I needed to understand the issues and the views of the people concerned as well as the environment, it involved a great deal of listening. So immediately there was a need to write down in a notebook (or tape recorder, although I never used one) what one had learned so that this could be reflected in whatever solution emerged.

At the end of each day, I would expect to have many pages of notes – and at the end of a week or two weeks, there were many, many pages of notes that could be difficult to absorb or analyse en masse. So the first step I took was to sit down at the end of each day and read through my notes and highlight everything significant that had been learned that day – generally 5-10 key points or lessons learned. This simple process of highlighting these key lessons encouraged me to think about them and they were more likely to become embedded into my wider thinking and, where appropriate, to adjust my approach to the work in hand.

Feeling it necessary to create a separate space where such key lessons could be learned and given both prominence and attention, I started a separate notebook called “LESSONS LEARNED” in which I wrote down (under the relevant date) each of the day’s lessons. Each evening I could not only read through the lessons of the day but also read through and remind myself of the lessons of the previous days. In so doing I built up a store of all the key lessons learned during the field work up to that point. At the end of the field work I had a list of all the key lessons that I had learned. These not only provided the basis for developing the recommendations to be made but these practical lessons could be quoted (duly anonymised when necessary) during discussions with those whom one was working.

This was a big step forward. However, these lessons learned included a wide range of issues – all mixed up together on the same page – such as foreign exchange rates/liquidity, land prices, the social status of women, weaknesses of the school curriculum, the effect of the seasons on a range of issues varying from market prices to the state of rural (mud) roads through to the incidence of hunger etc. When reading through these (jumbled) lessons, I found that they generally coalesced under a number of key subject (generally 10-15) – so I then created separate pages for each of these key areas and allocated each lesson learned to the relevant page. As a result, everything I had learned about currencies or the seasons or gender or politics could be found on the relevant page. However, as this was well before the digital era when everything was written in long-hand, writing them out a second time was a time-consuming process

So the next, logical, step was to prepare a list of key topics prior to starting the field work into which the lessons of each day could be allocated. One advantage of this was that it forced one to think hard about the issues likely to arise prior to starting the field work and to prepare a draft structure. Once on site the structure could be adjusted and any additional topics that became significant during the field work could be added in situ.

In January 2001, a year before the civil war officially ended, I was asked to lead a mission to Sierra Leone on behalf of DFID to assess what role it could play in supporting reconstruction and peace-building once the conflict was over (which happened officially in January 2002) [1]. At the time, there were signs that the war was beginning to end and it was possible to move around in some areas with appropriate military support. We were given 18 days of field work within the country to assess the situation and design a one-year project with a budget of £5 million that should start within a couple of months.

The aim was of the project was to support the many people returning to the rural areas from the capital and from refugee camps in Liberia and Guinea; to encourage the reintegration, in particular, of the many young people who had been coerced into joining one of the military factions (ex-combatants); and to provide some practical experience on which could be built a much larger programme of support. The UK team, working with a team of Sierra Leoneans, included expertise in health, farming, economics, logistics and security.

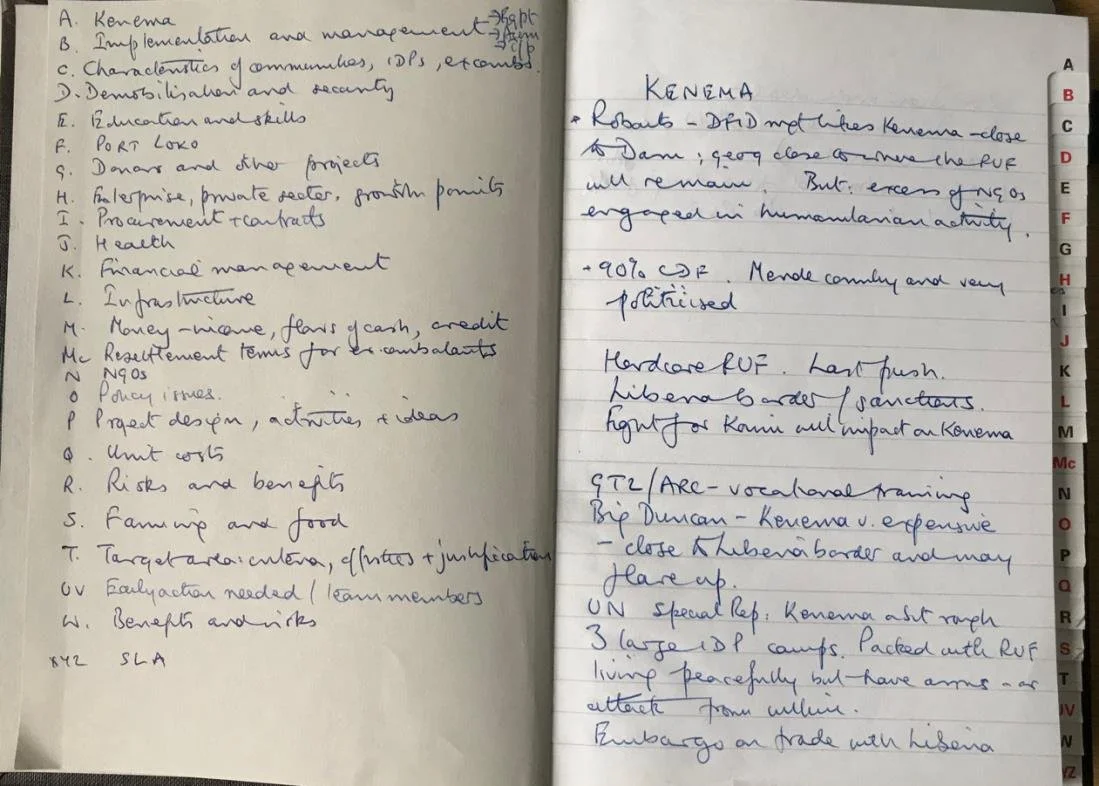

The headings from my lessons learned book can be found on the left overleaf (with Kenema and Port Loko being the two key areas that were asked to assess), whilst on the right-hand side are the first page of lessons I learned about Kenema. CDF is the {loyal) community defence force and RUF is the opposing Revolutionary United Front (guerilla force). IDP is internally displaced people.

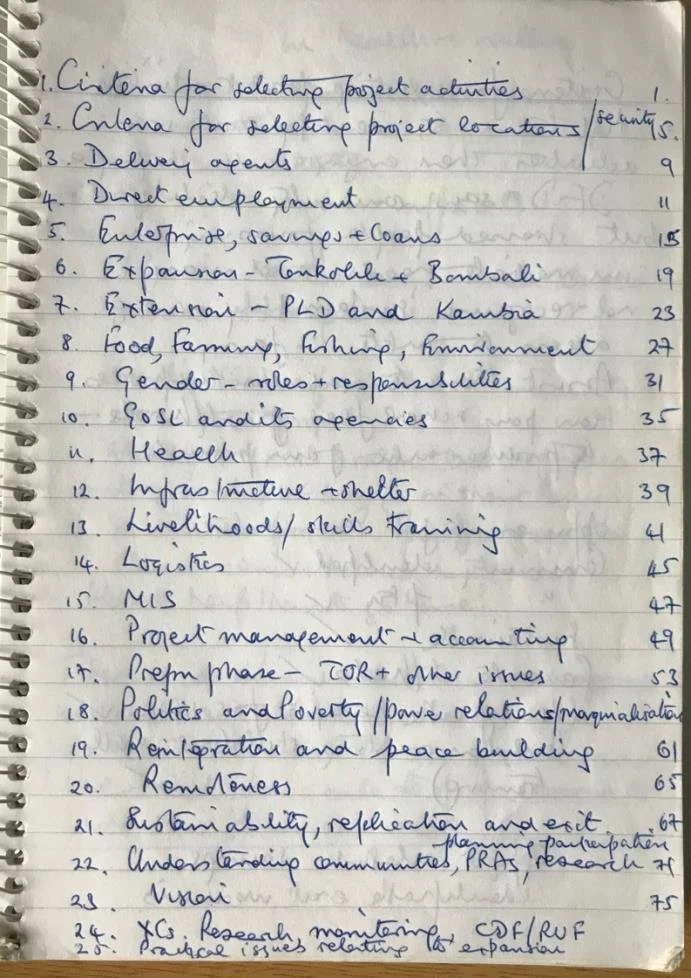

A priority for this first, pilot project that we were designing was to learn the lessons of experience from which to design a much larger project around a year later. My lessons learned index for the design of the second project can be found on the right, from which it is evident that there were other areas emerging – particularly concerning politics and the understanding of communities. Whilst planning the first project there were relatively few people in the rural areas whereas in the second phase there were many more, which provided the opportunity for much greater engagement and consultation.

Engaging with communities. A key element of project planning is to listen attentively to those who will be affected by the project. In Sierra Leone, it involved those whose lives had been so badly damaged by the war, as well as those who had been sucked into causing the damage (the ex-combatants) and who now had to be rehabilitated back into society. I soon became aware of the danger of making assumptions. For example, I blithely assumed that the first thing people would want to have is a secure supply of clean water. But in practice, people’s priorities varied significantly – for some communities, the priority was water, for others the school, for others the mosque or the church and for others the road to the village or some form of transport. I also assumed the best of everyone, but it soon became clear that there were those with vested interests (perhaps wanting to return to the status ante) and others who saw opportunities for exploitation within the chaos. In response to this, based on lessons I learned and in consultation with colleagues, I drafted a list of questions that we should ask ourselves before engaging in economic support to communities.

QUESTIONS BEFORE ENGAGING IN ECONOMIC SUPPORT TO COMMUNITIES

What are we trying to do?

Who are we trying to help?

Who is the target group?

Why do they need help?

•What are their aspirations?

What do they need (young, parents, elderly etc.)?

How many can be involved?

How can we talk to them?

What can they contribute?

What can we contribute?

Who are the opinion formers?

How mobile are people and goods?

Who else is helping them?

Who can exploit/take advantage of what we are doing?

What are the key sectors of activity?

What strengths are there in the local economy (if any)?

Where are the growth points?

Where are the building blocks?

What and who is capable of generating income?

What are the links between the various interest sectors?

What role can government play?

How can we map the resource assets and flows?

How do we avoid creating unsustainable monsters?

Who is capable of delivering/managing services?

Are there established norms for paying for services?

How do we build in flexibility?

How do we avoid building in dependency (upon technology, advice, finance etc?)

How do we achieve decentralisation without losing control?

How can we create liquidity in the system?

What are the local (existing or potential) areas of conflict?

Who owns the land and are there any land issues?

How do we build social capital?

How do we ensure that the poorest benefit?

How do we achieve transparency, participation and accountability?

Supporting enterprise in rural Liberia. Based on my experience in Sierra Leone, in 2004 I was asked to help in the rebuilding of the entrepreneurial sector in war-torn Liberia. The rationale was not only to stimulate economic activity and generate hope but also to find opportunities for the 120,000 ex-combatants (mainly young people of both genders) who had handed in their weapons and were being paid US$1 per day to keep them occupied in public works (such as cleaning the streets) or in vocational training. The former was soul-destroying and offered little hope whilst the second meant learning skills mainly by rote for which there were few – if any – jobs available. An additional need was to encourage these young people to get away from the cramped conditions of Monrovia (the capital) and their (former gun-toting) peers and return to their rural or small-town communities. Even this presented significant issues as much work was needed done in parallel to reconcile the abused and the abuser. However, the prospect of economic activity and meaningful work can play a significant role in finding common ground and encouraging reconciliation.

Although I had worked in Liberia previously, arriving back at the tiny airport building in the humid heat of the evening was a shock…getting through immigration, finding one’s case and looking hopefully amongst the dark faces in the dark night for a placard with my name on it. Once settled into my accommodation, and having accepted the inevitability of the continuous whine of the diesel generators, my priority was to get out into the rural towns, to walk the streets and to meet those who were engaged in some kind of business activity. The most common feedback from those I met was:

My building has been destroyed

My tools/equipment have been destroyed or stolen

I don’t have the liquidity/money to purchase raw materials or to employ anyone.

There is no market as people don’t have any money

It also became clear that a significant amount of donor money that was beginning to flow into the country for reconstruction (of schools, clinics and municipal buildings), and to supply goods (from tools to furniture), was going to a few, large contractors based in Monrovia. They had the capacity both to enter into large contracts (which governments like because they are easier to negotiate and to monitor) and to deliver what was needed. The downside was that the contractors brought their own staff from the city and that the funds (and profits) remained in the capital – and in many instances were remitted overseas to their largely foreign owners. The opportunity and potential to build the capacity of local entrepreneurs to construct smaller buildings and to supply furniture and tools (for these projects being funded by government) therefore became a priority.

From this emerged a project called the Rebuilding Artisans Project (RAP), which was developed as a means of providing a future for young people after 15 years of civil war, both those who had been involved in military activity (referred to as ex-combatants or XCs) and those who had been affected by it (referred to as “other war-affected people” or OWAPs).

During these visits to the county towns in the immediate post-conflict period it became clear that, whilst there was little economic activity, there were significant numbers of qualified and experienced artisans who had lost everything and who lacked the tools and liquidity to get going again. RAP was therefore designed to rebuild the capacity of these local artisans so that they could create local employment through providing goods and services to people returning home and for donor-funded infrastructure and construction projects; and that once re-established as businesses, they could provide apprenticeships to young people (both XCs and OWAPs) so that they could learn a trade whilst working within a business. Qualified trainers were also hired to provide more formal training in a structured way. Those who successfully completed an apprenticeship would benefit both from the skills and experience that they had learned as well as owning the tools with which they had learned. Discussions were also held with the Ministry of Education resulting in a formal, nationally-recognised certificate being awarded to those who successfully completed the year and achieved the required grades.

The idea of learning the lessons of experience in a structured way was built into the project from the start and involved everyone who played a role in its design and implementation. A series of headings was put together, which was amended over time in the light of experience, and everyone involved was required to record the lessons that they had learned each day. At the end of the month these individual lessons learned were given to a team member who consolidated them into a table which expanded each month. At the end of each month we would sit down together and go through them. The headings that emerged are listed below and a summary of the key lessons learned can be found in Annex 1. One of the key lessons I have learned about the process of learning lessons when you are working with a team of people – which could be just two to three of you or a dozen – is to routinely share with the team not only what you have learned together but how those lessons have been applied and with what effect. Like a feedback loop. As a member of a team, the knowledge that what you have learned has not only been noted but has also been applied and had some effect encourages you to continue recording what you have learned and sharing it.

REBUILDING ARTISANS PROGRAMME IN LIBERIA – a summary & lessons learned

An approach to rebuilding sustainable employment and a local capacity for donors to procure services in a post-conflict environment.

Selection and management of the artisans and apprentices,

relationships with local government,

the renovation of properties,

physical inputs,

contracts,

information to be provided to the business owner,

the supply and management of raw materials,

the supply and management of tools,

technical training, business skills training,

evaluating the apprentices,

stipends and feeding,

accumulating savings,

orientation and sensitisation,

keeping business records,

the future of the apprentices and artisans,

sanitation and health issues,

relationships with the wider community,

reporting and other issues.

Supporting enterprise in Namibia. Here are the headings for work I did in Namibia, which was looking at how funds provided from government to support local enterprise and employment could be more effectively used.

INDEX OF HEADINGS USED FOR LEARNING LESSONS - NAMIBIA JULY 2004

Agricultural Extension structure and activities

Business management skills

Business plan mechanisms/format/presentation/evaluation

Change – constraints to (physical, knowledge, financial, social)

Change – interest in/willingness to

Community structures, profiles and action plans

Crop farming/added value

Decentralisation

Financing - savings/capital accumulation/microfinance

Gender

Government role and activities

Group structure and dynamics

HIV/AIDS – incidence, impact and mitigation

IGA Fund – operations and projects submitted

Income sources diversification: farming based

Income sources diversification: non-farming based

Institutionalisation

Livestock farming/added value

Markets and marketing

NGOs

Other sources of IGA funding

Priorities for training/use of staff time

Private sector activity/scope for cooperation

Projects – approved and applications

Project Management

Recommendations

Regional differences

Relationships between departments and projects

Seasonality issues

Sector mapping (forestry/

SME Development

Sustainable livelihoods – human, physical, social, natural and financial

Tourism/conservation links

Vulnerability/shock factors

Youth

A move into social marketing. In March 2003 I was asked by DFID to be a member of a three-member team to review its £30 million investment in social marketing – to which my reply was “what is social marketing?”. As you can see in the box below, social marketing seeks to change people’s behaviour (generally linked to a product) by using the marketing and distribution skills of the private sector. Examples of this include encouraging condoms for reproductive health and control, encouraging the use of insecticide-treated bed-nets to prevent malaria or the use of filters or tablets to purify water. My role was to assess the impact of introducing these subsidised products on the conventional private sector.

I continued to be involved in reviewing social marketing projects for some time and then became involved in developing water and sanitation as a business – working with entrepreneurs to develop a market for their services. In preparation for working in Malawi in 2006 I prepared a list of all the issues around which lessons might potentially be learned - see Annex 1 below. It includes more than 200 topics and clearly for any one project it would be important to identify 10-15 priorities. However, this list proved very valuable as a point of reference – whether before planning meetings or before meeting a Minister – in that it helped to ensure that no topic – however small - was ignored within the entirety of the work.

AN ASIDE ON SOCIAL MARKETING

Social marketing. Social marketing is essentially seeking to change behaviour linked to a product. Older readers may remember “Clunk, click every trip”, which accompanied the introduction of seat belts into cars, whilst today the use of nicotine pads is encouraged to help people stop smoking. Social marketing began when Phil Harvey, a young American travelling in India, noticed both the high birth rate and the fact that Coca Cola (despite being a pretty worthless product) could be found in the remotest areas. Through his research he realised that this happened as a result of the product being manufactured by franchisees, through shrewd marketing (creating demand in the rural areas) and through the use of the existing distribution mechanisms that reached the last rural mile. All that Coca Cola owned was the formula for making the product and a large marketing budgeting. It owned none of the production facilities nor distribution channels.

What Harvey saw was the opportunity to use the same model – clever marketing and the use of local distribution channels – to encourage easy access to condoms to allow couples to control how many children they had. What he learnt can be found in his book “Let every child be wanted” and he went on from there to establish Population Services International (PSI), now the world’s largest social marketing organisation. The many positive developments that have taken place since then are not for discussion here – except to note that the essence of social marketing is the use of clever marketing to encourage people to regularly purchase an inexpensive health-supporting product (costing a few cents) that is available within a mile of where they live – distributed through the existing complex web of local distribution channels. These low-cost products that people purchase regularly are known in the trade as “fast-moving consumer goods” or FMCGs.

Expanding from condoms into water treatment tablets, the next target was the sale of insecticide-treated bed nets for the prevention of malaria. This initially proved a tough sell because the cost of a net was around US$5 – no longer an FMCG - but an item which many people considered as a capital purchase. So using social marketing techniques to move from a US$5 bed-net to encouraging the purchase of a toilet – costing around US$250 - is about as far as you can go from a fast-moving consumer good. It was a move that for a long time was considered impossible. And yet it happened in rural Bihar. The fact that it happened reflected there being a magnet to attract people, transparency around/confidence in the transaction and support mechanisms to bring the different parties to the point where a transaction – or a change – could take place.

Although I believe the constant and structured learning of lessons to be a very powerful mechanism, I have frequently found it difficult for people to adopt it. The typical answer I get is that this requires too much commitment and discipline – to which I suggest that, to make it easy, "at the end of the day just jot down what you learnt during the day and at the end of the week or the month just slot them into the relevant subject heading" – perhaps adding “if you don't have this commitment, then perhaps you shouldn't be involved in the project”.

ANNEX 1. LESSONS LEARNED – MALAWI WATSAN - POTENTIAL SUBJECT HEADINGS

Ability to pay

Access

Accountability

Accounting and auditing

Activities

Adapting to experience in the field

Adding value

Additional data needed and how to collect it

Affordability

Analysis – of products

Aquifers

Associations

Banks and banking

Benefits – arising from the project/investment

Benefits – sharing of

Branding

Breakages

Budgets – project, household, departments….

Cash, handling of

Cash flow

Champions (role for)

Charges and tariffs

Children

Choice – of technologies

Churches and mosques – their role in education and nurturing

Clientele

Climate change – likely effects of, adaptation and mitigation

Clinics – their role in awareness and education

Collateral and equity issues

Committees – form and function

Commitment

Communications

Community associations

Comparative advantage

Competitiveness

Competition

Conflict – managing and resolving

Congestion

Constraints (e.g. to uptake)

Construction

Consultation

Consumption

Containers

Contractors

Contracts

Controls

Convenience

Cooperation – potential for

Corporate status (sole trader, partner, limited company etc)

Corruption and rent-seeking

Cost data (basic/unit)

Cost of money

Cost-effectiveness

Cost recovery

Costs – fixed

Costs - recurrent

Credit – existing and potential suppliers

Criteria for intermediaries and suppliers

Customers

Database

Decision-making

Delegation

Demand

Design

Discounts

Disease transmission

Distribution

Diversification (of income and business activity)

Documentation

Donor activity and interests

Education – role of the educational system

Employment issues, costs & legislation

Enabling environment (for private investment)

Energy – current and future sources of

Energy – cost of

Equipment

Evaluation

Expectations

Finance – needed, available and sources

Flexibility

Forecasts

Frameworks

Franchising

Funding

Gender issues

Geographical coverage

Government institutions (relevant to the work)

Government policy and regulatory framework

Growth

Guarantees

Handbooks and guides

Handling (of people, customers, materials)

Health issues

Hidden costs

Holistic approach – neither water nor sanitation exist in isolation from the wider needs of communities

Hydrology

Hygiene

IEC (information, extension & communications)

Illegal settlements

Immovable objects (things that you cannot change – people, policy or practice)

Incentives

Income – levels and sources

Income – uses of, priorities for spending

Indicators

Information – sources of

Information technology

Infrastructure

Injury

Innovation

Insurance

Institutions – existing and their relevance; new ones needed

Interfaces between different parties

Investment

Job creation

Justification – for the project

Kiosks

Land tenure, rights and access to

Landlords

Latrine improvement

Latrine and latrine types/options

Leakages – of water and of money

Lease agreements

Legal status

Legislation

Linkages

Local consultants and their needs

Location (of business)

Losses (water, funds ………..)

Maintenance

Manufacturing/making things

Management

Mapping

Markets and marketing

Market research

Market segmentation

Market share

Measurements – standards for, frequency of

Media

Mentoring

Meters and measurement

Middlemen

MIS

Money circulating in the system (capacity to support increased business activity)

Monitoring and evaluation

Monopolies

Networking

NGOs

Objectives

Opportunities

Organisation – form and function

Participation (by communities)

Partnerships

Payment – rates of

Personnel

Pipes

Place (importance of the site)

Plans and planning

Policy (e.g. of government)

Politics

Population – growth and implications

Potential partners

Poverty

Power – sources of

Preferences (of consumers)

Premises

Pricing and prices

Principles (underlying) and guidelines

Priorities – of communities

Privacy

Private sector providers

Procurement

Products

Profit and loss

Projects (other) relating to this initiatives

Project design

Promotion

Public relations

Pumps

Qualifications

Quality – of water (or other entity)

Quality control

Queuing

Reading of meters (accuracy and frequency)

Recommendations

Regulation

Relationships

Repayment

Reporting

Research

Resilience

Retention (of staff, funds etc)

Return on investment

Rewards

Risks

Route map

Rural incomes and remittances

Rural-urban links and migration

Safety

Safety nets

Sales

Sanctions

Savings

Scale – growing to

Schools – watsan in the curriculum

Security

Selection procedures

Services

Shelf-life – of products

Sickness

Skills

Sludge – handling, disposal, utilisation

Small-scale vs. large scale projects

SME business development organisations

Social protection

Sources of funds

Sources of water

Spare parts

Spoilage

Staffing and employment

Stakeholders

Standards – for water quality, for water points…………….

Strategy(ies)

Storage

Subcontracting

Subsidies

Suppliers

Supply chain

Surveys – data from, quality of

Sustainability

SWOT

Taps

Tariffs and charges

Targets

Taxation

Technical assistance

Technology (level of and appropriateness)

The target group

Theft

Tools – to do the job

Trade unions

Trading

Training and trainers and their needs – of staff, of operators, of communities

Transition

Transparency

Transport

Trust

Urbanisation

USP (ultimate selling point)

Utilities

Vandalism

Vehicle management

Vendors

Viability – of businesses

Vulnerability

Wastage

Waste disposal

Willingness to pay

ANNEX 2. INFORMAL NOTE ON RAP – REBUILDING ARTISANS PROGRAMME IN LIBERIA2

An approach to rebuilding sustainable employment and a local capacity for donors to procure services in a post conflict environment.

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES. The Rebuilding Artisans Programme (RAP) was developed in Liberia as a means of providing a future for young people after 15 years of civil war, both those who had been involved in military activity (referred to as ex-combatants or XCs) and those who had been affected by it (referred to as “other war-affected people” or OWAPs). At the time (October 2004) public works programmes, mainly managed by NGOs, were employing large numbers of XCs and OWAPs. The programmes were valuable in providing employment and income, and a mechanism through which the process of reconciliation could be supported. However, both public works and NGOs were entirely dependent upon the flow of donor funds and neither offered a long-term future for the XCs or the OWAPs. The need was for the development of sustainable activities that offered a long term economic future to those involved.

During visits to the county towns in the immediate post-conflict period it became clear that whilst there was little economic activity, there were significant numbers of qualified and experienced artisans who had lost everything and who lacked the tools and liquidity to get going again. In addition, donor-funded programmes that were helping to rebuild the infrastructure were awarding contracts to mainly foreign-owned companies based in the capital (Monrovia). RAP was therefore designed to rebuild the capacity of local artisans so that they could create employment through providing goods and services for people returning home and for donor-funded infrastructure and construction projects; and that once re-established as businesses, they could provide apprenticeships to young people (both XCs and OWAPs) so that they could learn a trade whilst working within a business. Those who successfully completed an apprenticeship would benefit both from the skills and experience that they had learned as well as owning the tools with which they had learned.

THE EXPERIENCE OF PHASE ONE. The first phase of the project involved 25 artisans in three county towns engaged in carpentry (17), masonry (5) and blacksmithing (3). Selection of both the artisans and of the apprentices was not easy since conflict had barely ceased and only a few artisans had returned home from the capital, from camps or from neighbouring countries. Amongst the young people there was also still much antagonism resulting from the war. Despite this, 25 artisans in three rural county towns participated with nearly 600 (often disaffected) young people as apprentices.

For each artisan the project rebuilt the workshop, provided tools and raw materials for both artisans and apprentices, paid the land rental for three years, paid $30 per month per apprentice and paid for the technical/business skills trainer and the exam fees. The contribution of the artisan was to build a mud brick store, a toilet and washing facilities; install bamboo mat walls; provide lunch for the apprentices; keep records and run the business as a going concern.

[2] This programme was developed as part of the USAID-funded Liberia Community Infrastructure Project managed by DAI. DFID funded phase 3 of RAP. RAP was designed by John Meadley

It was clear from the beginning that an artisan who is trying to rebuild his business and to hone his practical skills after years of absence due to civil war is not in a position to also undertake the day-to-day training of the apprentices. This was therefore delegated to a qualified trainer – the kind of person who might otherwise have been working in a vocational skills centre – working to an agreed syllabus tied into national standards of vocational training, to ensure that the apprentices received an acceptable and consistent level of training. As such standards did not exist in Liberia these were developed in cooperation with the Agricultural and Industrial Training Board – an organisation that itself had to be rebuilt before it could fulfil this function.

The average direct cost of rehabilitating an artisan in Phase 1 was around $4,500 (of which rehabilitating the workshop – in most cases a complete rebuild - cost around $2,500) and land rental a further $600. However, at least 2/3 of these costs (building and tools) comprise the fixed assets of the businesses and should last at least ten years. The direct cost/apprentice varied from $500 to $1,000 – of which the per diem took $240. The cost/apprentice for tools varied from $180 for masonry to $500 for carpentry [3]. These costs relate to the immediate post-conflict period and were significantly lower in later phases, particularly in urban areas.

A review of Phase One in November/December 2006 showed that 93% of those apprentices who started were still involved at the end, 83% of them graduated, around 30% were still working with their artisan, around 15% were identified as working for themselves (likely to be higher than this) and 5% working for another artisan; most of the reconstructed buildings were still in good condition; the level of current business activity varied significantly, with some operating at full capacity and a couple clearly struggling; sanitary arrangements were still not perceived by most business owners as a priority; all of the artisans had 10-year rental agreements in place; around 85% of all the tools that had been provided to the artisans were still available; the technical training was considered to be good but the business management training less so; artisans were happy with the basis for selecting the apprentices – which they did themselves; the extent of problems with discipline varied greatly, but some managed the process much better than others through adopting a participatory approach; 70% of the businesses were formally registered with Government and paying basic licence fees (previously none were).

EXPANDING RAP TO THE CAPITAL – MONROVIA. In 2005 a decision was made to replicate RAP in the capital - Monrovia – learning the lessons from Phase One. It became clear that some changes were needed. Whilst land/space was not a significant issue in the county towns, it was in Monrovia. Issues of security were far higher and it was clearly not possible to repeat the high levels of investment needed in the carpentry sector – by far the most expensive. Surveys were undertaken both of the types of businesses available and also to identify which would be of interest to young people. The following businesses became priorities - bakery, woodwork shop, tailoring, barber shop, beautician, generator repair shop, radio repair shop, metal work shop, auto mechanic, bicycle repair, watch repair.

Unlike the county towns where businesses had been totally destroyed, in Monrovia the issue was mainly one of dilapidation due to the absence of income for maintenance. This significantly reduced the costs. For example the cost of rehabilitating shelters varied from $150 (tailors) to $500 (large bakery). Over 70 businesses participated, involving 447 apprentices.

FURTHER EXPANSION TO OTHER RURAL COUNTY TOWNS. In November 2006, a third phase of RAP was implemented in four other rural county towns of Liberia – including, for the first time, two counties along the coast. This phase involved 39 businesses and nearly 800 apprentices and was funded by DFID. New businesses brought into the programme included ocean fishing and fish processing, gold smithing and the repair of two-stroke engines. This phase built on the many lessons learned over time and involved much more detailed surveys prior to the selection of both the artisans and the apprentices, as well more thorough training of both. This became easier in the light of experience and as the social environment became calmer.

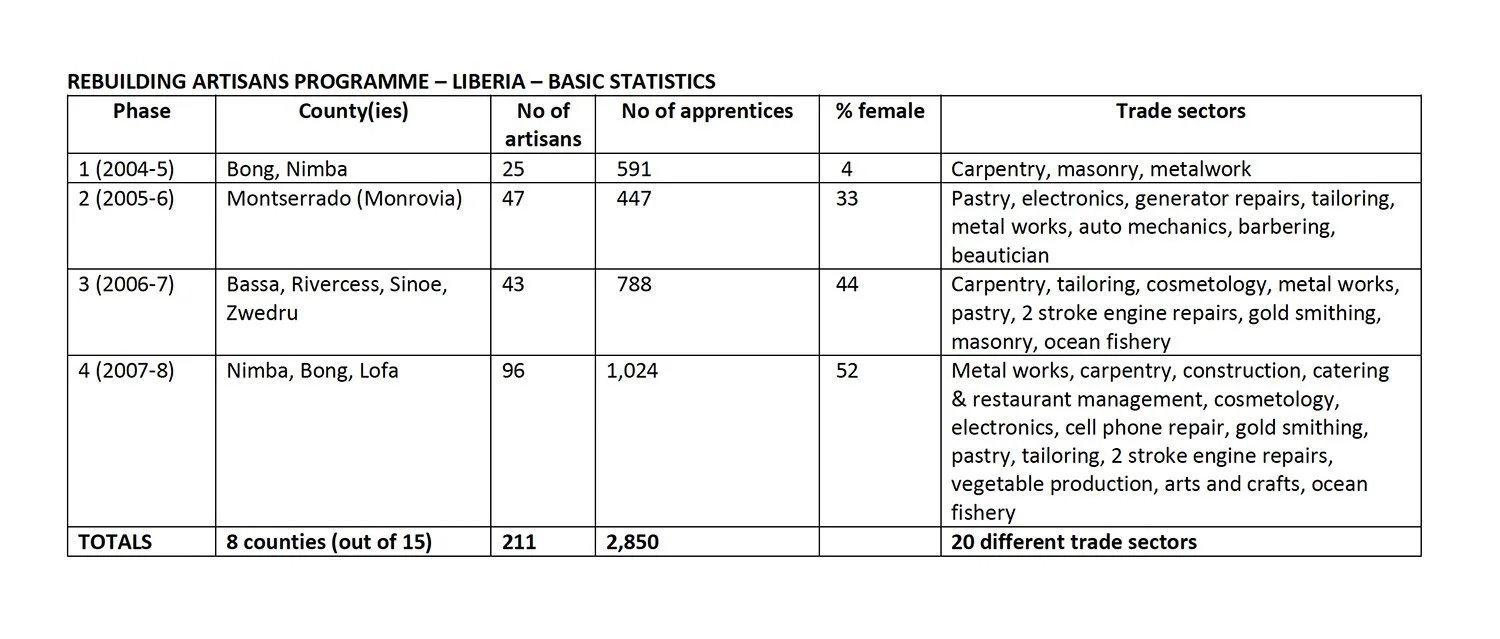

During 2007-8 the programme has been further expanded to smaller towns in the original two counties (Bong and Nimba) and to Lofa County in the north, bordering Guinea. This fourth phase involves 96 artisans and over 1,000 apprentices. Since the programme started in 2004/5 a total of 211 artisans and 2,850 apprentices have participated in 8 out of the 15 counties in Liberia, operating in 20 different trade sectors. Significantly the % of female apprentices has increased from 4% in phase 1 to 52% in phase 4.

LESSONS LEARNED. A wide range of lessons have been learned relating to the selection and management of the artisans and apprentices, relationships with local government, the renovation of properties, physical inputs, contracts, information to be provided to the business owner, the supply and management of raw materials, the supply and management of tools, technical training, business skills training, evaluating the apprentices, stipends and feeding, accumulating savings, orientation and sensitisation, keeping business records, the future of the apprentices and artisans, sanitation and health issues, relationships with the wider community, reporting and other issues.

APPRENTICESHIPS OR VOCATIONAL SKILLS TRAINING. An apprenticeship programme is not the only way of providing technical skills to young people, and many learn such skills in a more controlled and structured way through formal vocational skills programmes. However, in an apprenticeship young people are engaged in making things – or components of things – that are being built for customers and they become aware immediately of the importance of quality standards and meeting deadlines. Their chances of (continued) employment are better, whilst the wider community can see for itself its young people being usefully employed, learning skills and providing goods and services to their communities.

CONCLUSION. This programme has shown that rebuilding the capacity of experienced local artisans can, through apprenticeships, provide an economic future for young people in post-conflict areas as well as establishing a local capacity through which donors can procure services for reconstruction and rehabilitation. Many lessons have learned from this experience around which future initiatives of a similar nature could be developed.

[3] A conscious decision was made to provide top-quality Stanley Tools that should last a lifetime and not cheap Chinese, Brazilian or Indian tools.

KEY LESSONS FROM THE RAP AND MAP PROJECTS (as at 16 December 2006)

SELECTION AND MANAGEMENT OF THE ARTISANS

Nothing succeeds like success and the artisans selected for participation must be those who are either doing well or have demonstrated the capacity to survive in adversity.

Avoid raising expectations that cannot be met – particularly during the initial survey of businesses and the associated questionnaires.

Avoid the creation of pseudo-businesses – set up solely in order to participate in the project.

Artisans need to be continually reminded that they are not running a vocational skills training centre for the period of the project but are running a business to which apprentices are attached and being trained.

Avoid including too many artisans from within the same sector in one location, as the local market may not be able to provide enough business for all of them and for the apps that graduate.

There is a very wide variation in the capacity and commitment of artisans. At one extreme are those will treat the project simply as a training activity and give up when it is over and at the other end are those will perform well and invest in their businesses. In one case an artisan has invested over $20,000 in a new building and machinery.

In each location encourage the artisans to form into a group and encourage them to appoint a leader through whom information can be fed from and to the IP.

Many artisans continue to enter into verbal contracts after the EOP. The use of written contracts, duly probated where necessary, should be encouraged.

Some of the artisans revert to former (bad) practices (e.g. poor quality joints) when the project is over – due to laziness or because the customer does not specify exactly what is needed or because the price being paid is low. Artisans should be encouraged to keep copies of the standard designs of the major products in their shops to discuss with their customers; whilst donors and NGOs should be encouraged to include reference to these standard designs in their contracts.

Factors affecting the selection of artisans include:

a) Nationality – must be indigenous

b) Gender – preferably at least one third to be women

c) Running their businesses on a full time basis

d) Willing to contribute raw materials and labour to the construction of their new building.

e) Have the support of the community

2. SELECTION AND MANAGEMENT OF THE APPRENTICES

The number of apprentices in each business should reflect the nature of the business (e.g. a highly skilled business such as gold smithing can only employ around 6 apps whilst those for a fishing business may be determined by the capacity of the canoe) and the space available at the site.

The larger the number of apps the less supervision that can be provided to each and the more problems they can create.

25 apps is an absolute maximum. The maximum size of a manageable group is usually around 15, although others may be taken on bearing in mind that some will leave and in order to increase the return on the investment made in the artisan and his/her business.

All of the artisans seem to prefer the process whereby he/she is responsible for selecting the apprentices.

Selection criteria include:

a) Nationality – must be Liberian

b) Gender balance

c) Able and willing to commit to the apprenticeship full time

d) Immediately after conflict ends there may be a requirement to include a balance of former-combatants and of community people.

Artisans must be fully aware of the qualification requirements of those selected (as noted above) and be required to comply.

Avoid raising expectations that cannot be met

Apps must be made aware that at the end of the project they will only have reached basic level 1 and should not consider themselves as fully qualified.

Be aware that some people may be nominated solely to keep them quiet or in order to secure the stipend

If XCs are identified as such, they may feel indispensable/that the project was developed just for them; or they may feel stigmatized. This issue becomes less important the longer that peace has been established.

A letter of appointment should be signed between each artisan and his/her apprentices that lays down the undertakings of each. Templates for this are available.

A high level of discipline is essential within the shops, including attendance, application to the training, courtesy etc. Whilst the project will include basic rules of discipline within the letter of appointment, the apps should themselves consider and agree with the artisan the ground rules for the shop and the sanctions for breaking the rules. In this way, the apps are more likely to apply a degree of discipline amongst themselves.

Most artisans acknowledge the valuable role played by the counsellors in dealing with problems arising with the apps, particularly during the immediate post-conflict period.

3. RELATIONSHIPS WITH LOCAL GOVERNMENT

Cooperating with the local authorities. As peace becomes a reality, local authorities will begin to make their presence felt and require the payment of registration and licences and to implement the various regulations that existed before the war. It is important to keep these authorities regularly informed of the purpose of the project and of how it is progressing and to seek their support and cooperation. There is no harm in allowing the authorities to take some of the credit for the development that is taking place in their area of operation.

Registration. All businesses must be required to register with the appropriate authorities. Where the project starts towards the end of the financial year then it should be possible to negotiate with the authorities to register at the beginning of the next financial year. Such concessions from govt should be in writing.

The project should pay the cost of registration for the first year, to encourage the process. Once registered, the authorities will follow up subsequently to ensure future compliance.

Regulations. Identify at an early stage the regulations that will apply to the local businesses and ensure compliance. Relevant agencies may include the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Commerce, the Ministry of Health, the City Government and the Fire Service These may relate to location or the payment of various licences. Of particular relevance in Liberia is the sourcing of timber from the forests, bearing in mind the sanctions relating to the harvesting and exporting of wood. Such issues need to be properly addressed so that the project is not encouraging illegal or inappropriate activities.

Location. Most local authorities have strict rules about the location of different types of businesses – in terms of zoning or distance between buildings or from the side of the road. Businesses such as fish smoking (smoke pollution) or metal working (noise) may need to be located in specific areas. It is important to adhere to these regulations even if they are not currently being enforced, since in coming years they may be enforced and the project’s investment lost if premises are demolished.

4. THE RENOVATION OF PROPERTIES

Where properties have been totally destroyed then a new structure/shop will be necessary. If possible, design a standard structure – for ease of construction and purchase of materials – with modifications for different trades where necessary.

In all cases, the artisan should be required to contribute to the construction process. This may be just labour or it could be blocks, sand, timber and building supervision.

The basic standard design can be modified for the different types of enterprises. For example, a tailoring shop may require a smaller total area but with walls to the eaves for security; a fish processing business may require more storage space etc.

All designs (and modifications designs) should be numbered and dated and show the name of the designer. IPs should sign a dated receipt when they receive the designs from the project. There should be no uncertainty as to the version, the source or the date of receipt of the different designs.

Involve the potential artisans in identifying the most cost-effective source of raw materials suitable for the purposes required. This shows recognition of the local knowledge of the artisan and is likely to increase his interest and reduce his criticism.

The apprentices should be involved in the construction of the building.

All of the building designs (for the different types of enterprises) and related bills of quantities should be finalised BEFORE the project starts.

Issues of zoning to meet local government requirements will become increasingly important as peace is established. It is important to ensure that all buildings funded by the project meet zoning and other local government requirements.

Whilst training is under way it is important to have some form of walls or sheeting around the shop so that the apps are not distracted by what is happening outside the shop. This can be temporary in nature since once the training is over most artisans like the public to be able to see what is happening in the shop in order to encourage custom. If continued security is required, the original walls/sheets could be replaced by wire mesh.

Where existing properties are to be renovated, the work to be done must be defined by a trained and competent person and a specification drawn up. The contractor(s) authorised to do the work MUST be supervised.

A number of artisans have subsequently built extensions to their workshops – either for additional storage, working space, domestic use or toilets. Depending upon the extent of new build or reconstruction it is appropriate to have a policy on what is permitted during the project period.

5. PHYSICAL INPUTS. Ideally, all the physical inputs must be in place before the apprenticeship formally starts. This means:

The construction/repair of the premises is completed (although in some instances it may be possible to continue with the repair process during the first week or two, providing that there is security for the tools and raw materials);

The tools for both the owner and the apprentices are in place

The raw materials – or at the very least those needed for the work to commence

The books that the artisan is required to keep are in place

An attendance register is provided

A discipline book (with carbon sheets) should be supplied

6. CONTRACTS IN PLACE.

All contracts between the artisan and the IP must be in place before the apprenticeship starts. These include:

The lease agreement between the owner and the landlord. Ideally this should be for 10 years with the rent (including rent rises over time) pre-agreed. At the time of rent negotiation by the artisan, the landlord should NOT be aware that the rent is being paid by the project – otherwise the rental will rise sharply. In many instances a ten-year agreement may not be possible. Where premises are being repaired the agreement should be for a minimum of 3 years. Each agreement should be ratified by probate in the courts so that the tenant can take action is necessary, such costs being to the account of landlord and tenant.

Once the agreement has been finalised (and probated) between the artisan and the landowner, the payment of rent to the landlord should be made directly by the IP to the landlord and not to the artisan to pass on to the landlord. All such payments should be receipted.

A draft contract between LCIP (through its IP) and each business owner is already available, which clearly defines the obligations of each party. Experience shows that the artisan is unlikely to fulfil all his/her obligations unless the agreement is routinely monitored.

A draft contract between the business owner and each apprentice is already available, which defines the obligations of each party.

Whilst people may read these contracts before signing, most are then filed and forgotten. However, these contracts contain vital information concerning objectives and working practices, including in particular about the utilisation of sales income derived from tools and consumables provided by RAP, and must be routinely referred to in discussion with the shop owners.

Once the opening phase of the project is complete, the IP(s) should be asked to review the budget, identify any savings and submit a revised budget showing the priorities for utilisation of the available funds. Flexibility of this kind is essential if the project is to operate successfully.

7. INFORMATION AVAILABLE TO THE BUSINESS OWNER. For the purposes of transparency and proper planning, the business owner must have a copy of the following:

A list of all the tools that he/she and his/her apprentices will receive

A list of all the raw materials that he/she will receive for the running of the business and for the training of the apprentices

8. THE SUPPLY AND MANAGEMENT OF RAW MATERIALS

Access to raw materials (timber, cloth, fuel, cement etc) is fundamental to the operation of the business – even more so when there are 20 or more apprentices working.

The nature, quality and quantity of raw materials needed for each type of business must be identified early in the planning stage, and tested with the participating artisans. Involve the artisans in deciding what raw materials to purchase – both the type and the brand. This is most marked in the tailoring sector where a tailor cannot be expected to make and sell products with material his customers do not like.

At an early stage in the project the artisans should have a list of the items to be provided, together with the indicative delivery dates.

Raw materials MUST be purchased well in advance of requirement in the field, which may have some storage implications for the IP.

Assuming that responsible IPs are being appointed, they should be provided with funds to purchase all raw materials. Unless absolutely necessary, the donor or programme manager should not be directly involved in the procurement process, other than in the role of auditor, since it will rarely have the local knowledge to purchase what is actually needed and its internal bureaucracy may significantly delay the project.

Transport can be a significant proportion of the cost of supplying tools and raw materials. Transport costs will vary significantly according to location and to the season, the state of the road and the level of demand for transport from others. A significant contingency must be included for genuine increases in the cost of transport.

Significant quantities of raw materials will be supplied and converted into products for sale, the income for which is to be used for the replacement of stock as well as the income of the owner and the savings of the apprentices. At least for the life of the project, the artisan should maintain a stock record book that demonstrates when the (project) raw materials are drawn down, what replacement materials are purchased and how these in turn are used. In this way it is hoped that the artisan will begin to appreciate the importance of maintaining stock. The raw material stock book should be signed off by the IP each month.

9. TOOLS

The quality of the tools selected is an indication of the seriousness of intent of the project (including the donor and the manager). Cheap tools quickly break (particularly with inexperienced apprentices) and lower morale. In contrast, good quality tools are more likely to withstand the inexperienced hand and provide an income to the recipient for a lifetime.

The tools must remain the property of the project until the end of the project and only handed over when all obligations have been fulfilled by the artisan or the app.

The IP should check that all tools are still available each month, and any shortfalls recorded.

The project should arrange for occasional but thorough spot checks of the tools in the shops of the artisans.

Apprentices must be taught preventative maintenance of their tools and be sanctioned for not applying the rules that they have learned.

Tools must be kept in a secure place and issued daily against signature. Lost tools must be paid for, unless there is proof of theft by a third party.

Tools should be purchased directly by the IP, duly audited by the donor and be held responsible to both donor and artisan for so doing, and not directly by the donor itself – where bureaucratic delays are inevitable.

Funds must be available for spare parts and accessories and also for basic maintenance equipment (e.g. saw sharpeners). The IP should check the status of the tools each month and, where there are moving parts such as with a generator, check that proper maintenance has been done. Evidence for this must be provided such as a receipt for servicing or for the purchase of oil or filters.

Where local artisans are capable of producing tools required by the project’s artisans, the IPs should be required to purchase from them. However, local artisans are likely to require time to make them and this should be built into the project timetable.

A list of tools that each artisan and each apprentice will receive must be given to the artisans no later than the orientation workshop.

Experience has shown some shortcomings in the tools and raw materials provided in different sectors. These include:

a) In the woodworking sector there is need for good quality hand drills and bits, G-clamp, ripping saws and saw sharpeners.

b) In the metal working sector the artisan, given the raw materials, can make many of the tools. Raw materials not supplied include angle iron, flat bars, pipes, steel rods, angle bars, welding rods.

c) In the masonry sector there is need for significantly more raw materials (particularly cement) and for block making machines.

10. TECHNICAL TRAINING. The following arrangements must be made before the project starts, with copies issued to the relevant parties. This should cover not only technical training but also training in business skills.

The syllabus must be designed, copied and circulated to the business owners.

The syllabus should meet national standards and ideally will be provided by the appropriate national authority.

The syllabus to be used should be numbered and dated so that it is clear which version of the syllabus is being used.

Where possible the issuing authority should provide a signed and dated letter alongside the provision of each syllabus and the IPs should in turn sign to confirm receipt of each dated and numbered syllabus.

The syllabus should relate directly to the examination that the apps will sit.

Such training manuals (or other training materials) as will be required for the owner to implement the apprenticeship should be designed, copied and available for distribution to the apprentices by the owner when needed.

If it is possible to arrange for some formal certification by the AITB, then this should be done. As far as possible, the training process should fit in with the national training standards and structures.

The syllabus should not be rigidly time-bound – as this may constrain the operations of the business. As far as possible, training should link in with the jobs as they become available.

The more uncommon the sector (e.g. goldsmith or fisherman) then the more important it is to anticipate the difficulties of having available a comprehensive syllabus or an experience teacher – and plans should be made accordingly.

Good instructors are not easy to find. In general, it is preferable to appoint instructors from the locality, who understand the local culture and who will normally have their own place to stay. Whilst salaries should ideally reflect local salary scales, the budget must include some contingency to cover the additional costs of recruiting trainers from outside the locality if necessary.

The views of artisans varies re the need for the apps to be literate and numerate. However, in general this is a significant advantage and ideally basic training in both literacy and numeracy should be provided.

Some artisans are not happy about having a technical trainer in their shop, particularly one who is receiving a reasonable salary. Such potential resentment should be identified before signing contracts and the artisan changed.

Other artisans have opted to become technical trainers (for the salary) and handed their shop over to someone else for the period of the project. This causes confusion at the shop and the performance of such shops is significantly lower than those where the artisan is must be present and operating the business on a full time basis.

A competition between the apps in each sector could be introduced – e.g. the best product made from used Coca Cola cans.

11. BUSINESS SKILLS TRAINING

A simple syllabus is needed for business skills training. Such training as is provided should be elementary and cover only the basics – giving particular emphasis to estimating costs, marketing and keeping records.

The technical partner, the IP and representative business owners in each sector should work together to develop a simple business model for each sector, which identifies the major costs (overheads and consumables) and relates this to the potential income. Information derived from the monthly reports and other records can then applied to this model, in order to refine it into a working tool for the business owners and apprentices and be incorporated into the business skills training.

Both artisan and owner should learn from the actual records they keep each month in order to learn their value.

12. EVALUATING THE APPRENTICES

The basis for evaluation of the apps must be in place before the project starts.

The evaluation should be independent and comprehensive.

Ideally this will be done by an independent agency of national standing (in Liberia this is the AITB and the relevant Ministry).

The testing must be linked directly to the actual syllabus used in each sector.

The testing should take place over a period of time and cover both theory and practical.

The certificate that is provided to those passing the tests should have national standing.

• Making the testing process more thorough and more searching means it is more costly and adequate funds must set aside for this.

13. STIPENDS AND FEEDING

The apprentices need to eat and to have some income to pay for their personal needs. In Phase 1 the apprentices were given a stipend – in line with other donor-funded public works projects – whilst the artisan was required to operate a black pot to feed the apprentices. In practice, some apprentices came solely to get the stipend whilst many artisans struggled to operate the black pot, either genuinely through lack of funds or through lack of commitment.

Where there is a DDRR programme under way that pays stipends, it may be essential to do the same. Where this is not the case, other options are possible.

One alternative approach is to provide for/fund the black pot, so that the apprentices can earn their income (with the agreement of the artisan) either through doing paid overtime work or through securing petty contracts in their own time. A good meal is worth a great deal to those who have little and serves to encourage the apprentices to join, stay and work hard.

14. ACCUMULATING SAVINGS

Attempts to encourage or require artisans to save funds on behalf of their apprentices have generally not worked, at least not in any volume. There appears to be no sense of moral obligation to do so – or else a lack of understanding of what is required.

Each artisan receives significant levels of raw materials for his business (varying from US$500 – 1,000), which when sold will increase in value by up to 50%. This income will have no associated costs (raw materials from the project and the app labour is free), hence part of this income must be set aside as savings for the apps (issue is addressed in the letter of appointment of the artisan).

All parties seem unable to trust anyone else with their money

A number of apprentices have saved funds – either alone or in cooperation with others on the Susu principle. This should be encouraged.

If a minimum amount of savings to be set aside for each app is stated in the contract with the artisan then most artisans will provide only the minimum.

The basis of saving for the apprentices or of providing capital to the apps at the end of their participation in the programme should be made clear at the beginning. In some cases artisans want to share income with the apps as contracts arise. This has merit, providing that the amounts distributed on each occasion are recorded for future reference. The down side is that small amounts of money received routinely are easily dissipated on immediate needs so that there is no capital available at the end. Hence the amount of funds shared with the apps during the project period should be small with emphasis on building up savings for the end of the project. This requires a reasonable level of bookkeeping and a degree of trust between the owner and the app. This is not easy to achieve in an immediate post-war situation.

The amount to be set aside each month from earnings should be decided by the IP and the artisan based on the income earned – which will have been generated using raw materials and labour funded by the project. It is possible, but not certain, that this can be based on a % of net earnings. This possibility should be assessed.

The record keeping system should include the funds set aside as savings for the apps and should be checked and signed off monthly by the IP.

In addition to what the artisan may do, it is good to encourage the apprentices to save such income as they can afford through which they can finance their future after the apprenticeship is over.

15. ORIENTATION AND SENSITISATION.

Although people have learned through apprenticeships for centuries, RAP has some new features of which the owners must be aware. The apprentices are learning within the atmosphere of a vibrant business, in which there is a syllabus to be delivered (flexibly) to a defined schedule. There are clear codes of conduct and of discipline. Stocks of consumables are being provided that must be replaced. Records need to be kept and procedures followed.

A workshop needs to be arranged for all the business owners, so that appropriate orientation can take place. In turn, the artisans must sensitise the apprentices of all the key issues – ideally in the presence of a member of the IP to ensure all issues are covered. These should also be reflected in the agreement between the artisan and the apprentices.

Experience shows that, once the project is over, artisans may revert to some of their old production habits – for example not using proper joints when making wood-based products. This may in part be due to the price paid by the purchaser (whether private or NGO) or simply laziness. For many products, particularly those that are purchased by government or by donors, there are standard designs that stipulate the size, the amount of each type of material used, the type of construction (e.g. joints, use of nails, type of welding etc) and the level of mark up that is acceptable. If such designs are available, then they should be introduced and explained at the orientation workshop and may subsequently be the focus of sector-specific workshops on cost-estimating. The project can also encourage all donors and NGOs to adopt such standard designs so that they become an integral part of contracts issued by donors and NGOs to artisans.

16. KEEPING BUSINESS RECORDS

Record keeping is one of the most fundamental requirements for growing a sustainable business and very few artisans keep records of any kind.

Record keeping is currently abysmal. Most artisans do not understand the value of records and see it solely as an obligation of the project. The business skills training needs to be adjusted so that more emphasis is given to demonstrating how records can be used to increase the profitability of the business.

The main reasons for not keeping records are a lack of understanding of the value that the records can play in the operations of the business and a fear that the information will be passed to the revenue services.

Those few artisans who do keep records do so because they believe it is a requirement of the project. This view is reinforced if the records books provided by the project have the names of the donor, the IP and the project written on the cover. Each set of record books should have the name of the relevant artisan on the front and, where appropriate, on each page. Sufficient of each book should be provided to each artisan to last well beyond the life of the project.

The record books of each artisan should be checked monthly by the business skills trainer and signed off – noting either that the records are satisfactory or, if not, indicating what needs to be done to bring up to the required standard. The IP should countersign as confirmation of the findings.

The record books should be kept to the minimum – such as purchase ledger, sales book, cash receipt book and general ledger (with analysis columns).

Options to address record keeping include appointing a project bookkeeper who will maintain records for the artisans (probably unlikely to succeed due to a wish for confidentiality) or paying 50% of the cost of employing a bookkeeper, who would most likely be a family member.

Given the lack of appreciation of the value of the records, and the low level of commitment, another option is that the business skills trainer could be required to help each artisan to transfer the sales/purchase data into the general ledger and undertake a monthly analysis to determine the level of profit or loss. In this way, the artisans may begin to appreciate the value of records and their analysis.

17. THE FUTURE OF THE APPRENTICES AND THE ARTISANS

Artisans, trainers and counsellors must, through discussion, identify the hopes and aspirations of the apps and help them to plan to achieve them whilst the artisans must feel a responsibility for their futures. The IP should report each month on the extent to which this is being addressed.

Most of those apps who have qualified to date are not well equipped to set up on their own, although many have done so and are generating some income. They lack capital, technical knowledge beyond the basic level and the basic business management skills including cost estimating and record keeping.

After only 6-8 months training, those who set up on their own need continued oversight and this could perhaps be achieved through appointing a continued guidance and technical advice. This might be one of the artisans, one of the trainers or a third party appointed for the purpose.

The project will be quickly over and the artisans and apprentices will move on. In order to learn lessons and also to support them during this period when they may move from the sheltered environment of the workshop to the world outside, funding should be provided for some technical support and monitoring.

18. HEALTH AND SANITATION.

Issues relating to health and sanitation must be addressed during the project planning stage.

In order to raise the general standard of health, all shops must provide access to clean toilet facilities together with clean water for washing hands, although this will not be seen as a priority by most artisans. Failure to meet this requirement must be addressed by sanctions at an early stage – e.g. no toilet no tools!

Whilst the building of the toilet is the responsibility of the artisan, it is clear that in many urban situations the wider community also needs toilet facilities and people will break into toilets built by the artisans. It may therefore be necessary for the project to provide some support for an adjacent community toilet.

The basic requirements for the construction of a toilet should be laid down by the project.

The apprentices should be required, on a rota basis, to take responsibility for the cleaning of the toilet and the provision of clean water, soap and towel.

The issues of medical care and of dealing with injury will be raised by the apps. It is not possible for the project to become involved in providing medical care nor to accept liability for injury in the workplace of the participating artisans. The project may wish to provide a medical kit to each artisan and require that the training must emphasise safety in the workplace. Apart from these measures the responsibility for the medical care of the apps should rest with the artisan.

Issues relating to medical care should be addressed in the letter of appointment to the artisans and apprentices.

19. RELATIONSHIPS WITH THE WIDER COMMUNITY

All the artisans operate within a community, whilst the young people selected as apprentices (particularly the XCs) will be the concern of the community. The process of selection means inevitably that some (both artisans and apprentices) will be chosen and others will not. Engaging the community, through elected representatives, elders or community organisations, can help to identify the most appropriate participants and also to limit the damage that could be caused by those who are not selected.

At the same time, community leaders can reflect local bias in favour of certain groups and they should not be given the impression that they will choose the artisans or apprentices.

Disaffected people can damage the programme through misinformation and through demanding payment from those selected as artisans or apprentices.

20. REPORTING. A simple system of monthly reporting must be put in place. A copy of the draft monthly reporting schedule for RAP is attached, from which it can be seen that the focus is on attendance, progress in training, levels of business activity and raw materials stocks. Other issues to be touched on should include the aspirations/future of the apprentices (which should be considered routinely), issues of conflict resolution and relations with the community. A special section should be for lessons learned, which should be carefully recorded and consolidated under key headings for future reference.

21. OTHER MEASURES. The further that the country is from the time of conflict, the wider the range of issues that may arise. These include environmental issues such as the sourcing of raw materials (e.g. precious minerals or timber) that might be sourced illegally or without the appropriate permits. These issues should be borne in mind from the beginning, even though they may officially rise to the surface only after some time.