THE POWER OF CREDIT AND THE CURSE OF DEBT

A very personal perspective focused on farming.

“Poverty covers people in a thick crust, making them appear stupid. Credit unlocks their humanity”. After five decades engaged with rural communities in rural Africa and Asia, those words from Muhammud Yunus [1] continue to ring true. I had not been many weeks into my first job in 1968 – at the Swaziland Agricultural College – when I began to appreciate the vital role that entrepreneurs play in creating both wealth [2] and employment. I have since both worked with entrepreneurs and been one myself – in 1983 launching a company to both partner with, and support, entrepreneurs in Africa and Asia. Some were making things and others trading. My interests extended through farming, malaria prevention, water purification and distribution, sanitation, medical services and even the pelleting of the spores of mycorrhizal fungi to impregnate the soil when replanting Pines and Eucalyptus in the Philippines following lethal mudslides. These entrepreneurs made a living for themselves and for others whilst supporting the welfare of their community.

I have also seen how small amounts of credit, either alone or alongside a range of other services, have transformed the lives of individuals and communities.

In 1993, friends and family raised £700 to help a family in Ghana to establish a small plant making gari (roasted cassava). The loan was repaid (with interest) and recycled within the community for a further decade – financing many women to start businesses making soap or dressmaking, petty-trading or baking.

In 1993, I became responsible for DFID’s first project focused on businesses with growth potential – over seven years supporting around 150 such businesses in Ghana. A range of services were available – business skills training, subsidising the cost of a qualified bookkeeper and of producing a business plan, bringing out 125 retired British executives to provide peer-to-peer support whilst also training the bankers to better understand how to work with entrepreneurs [3].

For many there was a genuine need for credit to purchase key assets or provide working capital. But even with professional accounts and a business plan many could not meet the banks’ requirement for collateral. In response we set up what we believe was the first corporate mutual guarantee scheme in Africa [4].

[1] The founder of the Grameen Bank

[2] In its original sense of “those things necessary for our welfare and prosperity

[3] A programme focused on relationship management delivered in partnership with Durham University Business School.

[4] A group of <12 entrepreneurs who know each other well & form a simple corporate entity registered with the bank into which an agreed amount is paid each month to create a bond that provides security to the bank.

Corporate mutual guarantee scheme. One of the first beneficiaries was Alaska Joe, then a small-time carpenter in central Ghana working only with hand tools, who got his first ever loan - for a machine planer. When I returned to Ghana more than 20 years later, after surviving a bear-hug that left me winded, he showed me his large furniture-making factory and the residential properties that he had constructed and was renting out.

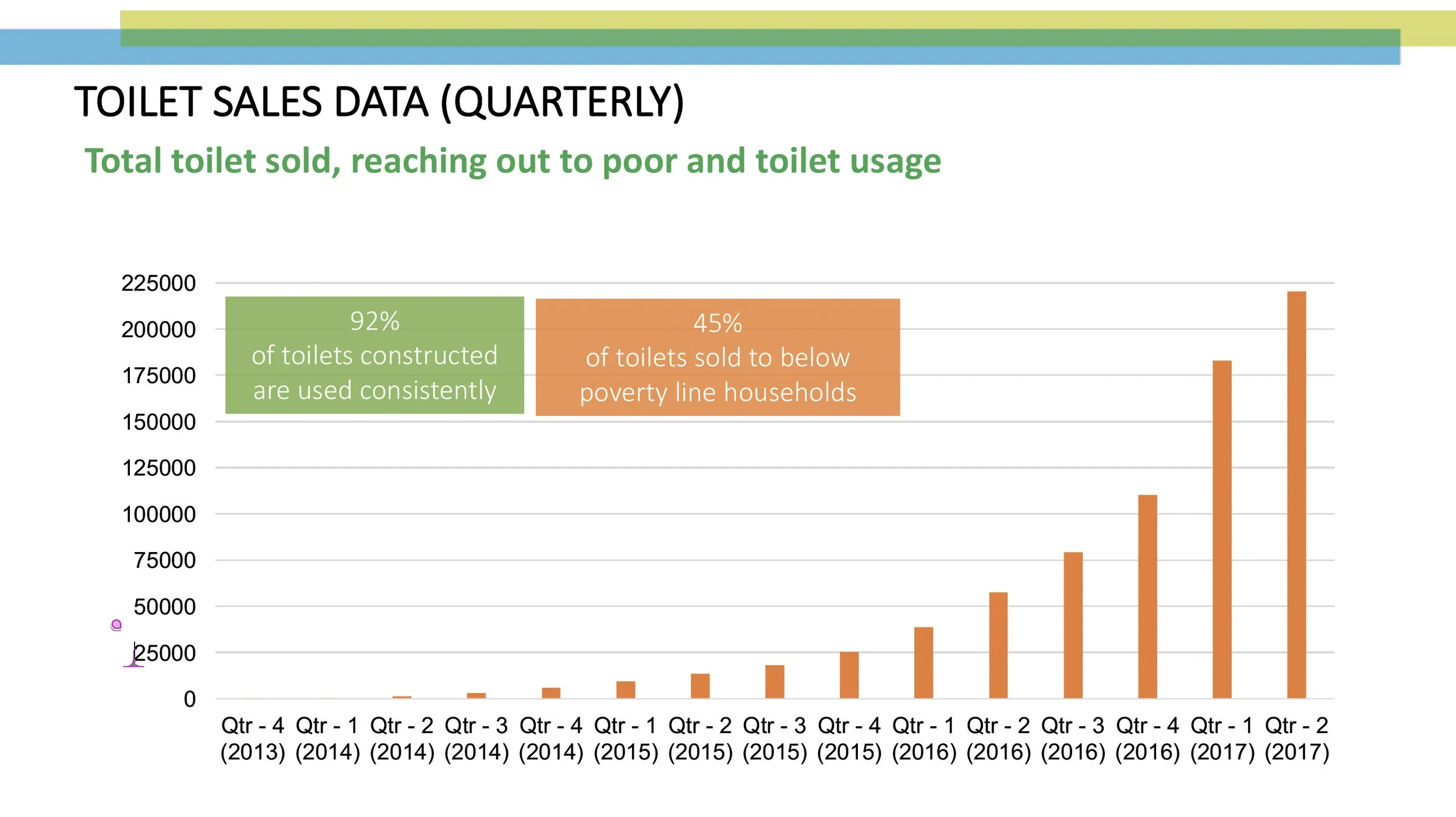

Building a market for toilets in rural India. For six years, I was involved in rural Bihar (India’s largest and poorest state,) working with Indian colleagues to encourage the construction of household toilets on the basis of willing buyer-willing seller rather than through charity or public provision. Once concerns around design, construction, quality and culture had been met, and demand began to take off, it was access to credit for the poorest that took sales to scale - through the spider’s web of women’s self-help groups. An Indian friend who started the first of these groups in Bihar told me: “It is said that once you are financially sound many things take place. Most of the women whom we supported had no toilets at their home. When we talked they expressed their pain of open defecation, so we started financing for their toilets too and now 98% of women farmers we are financing are having toilets at their home, and it is a big changer for their quality of living. They can also send their children to school, particularly important for their daughters because it increases their marriage age”.

But a loan that appears as a credit on one side of the balance sheet appears as a debit on the other. Derived from the Latin word Credo (to trust), alternative words suggested by the thesaurus are positive and include approval, merit and esteem. Debt comes from the Latin word Debito (to owe), and alternative words suggested in the thesaurus are negative and include outstanding payment, dues and arrears. Debt is the dark side of the financial coin.

Allow me to focus on the world of farming – with which I am best acquainted. Over recent decades farming has become increasingly industrialised… more “efficient” in purely economic terms but more inefficient in biological terms [5]. There are relatively few Western farmers for whom debt is not a significant issue. How they farm is determined as much by the need to keep the bank happy as by government policy (and subsidy) and global markets. Farming based on what is good for the land or for community is a luxury for the few. In the example below, debt has increased significantly to achieve the economies of scale required to meet the continued downward pressure on prices. Although keen to take the rest of the farm regenerative, that option is heavily constrained by the need to service the accumulated debt.

Example of mixed arable farm of 110 ha – 20% committed to free range egg production

% of NET income generated by each enterprise.

57% from free range eggs (from 20% of the land)

4.5% from renewables

11.5% from contracting

13.5% crops

13.5% from lets

What aspects of your farm do you consider to be “non-regenerative” and what constrains you from taking the whole farm regenerative?

The free-range egg enterprise is heavily reliant on imported soya, fishmeal etc which is a common problem for all in the

poultry sector.

The buildings are also static so unable to be rotated within a rotation – therefore the build-up of parasites (worms) has to

be routinely treated with wormers.

The reliance on chemical fertiliser is a concern on the cropping although we have been using strip-till (non-inversion) for

nine years and incorporating FYM and poultry muck to improve organic matter and soil health.

The high level of debt associated with the chicken enterprise – reducing flexibility in changing direction

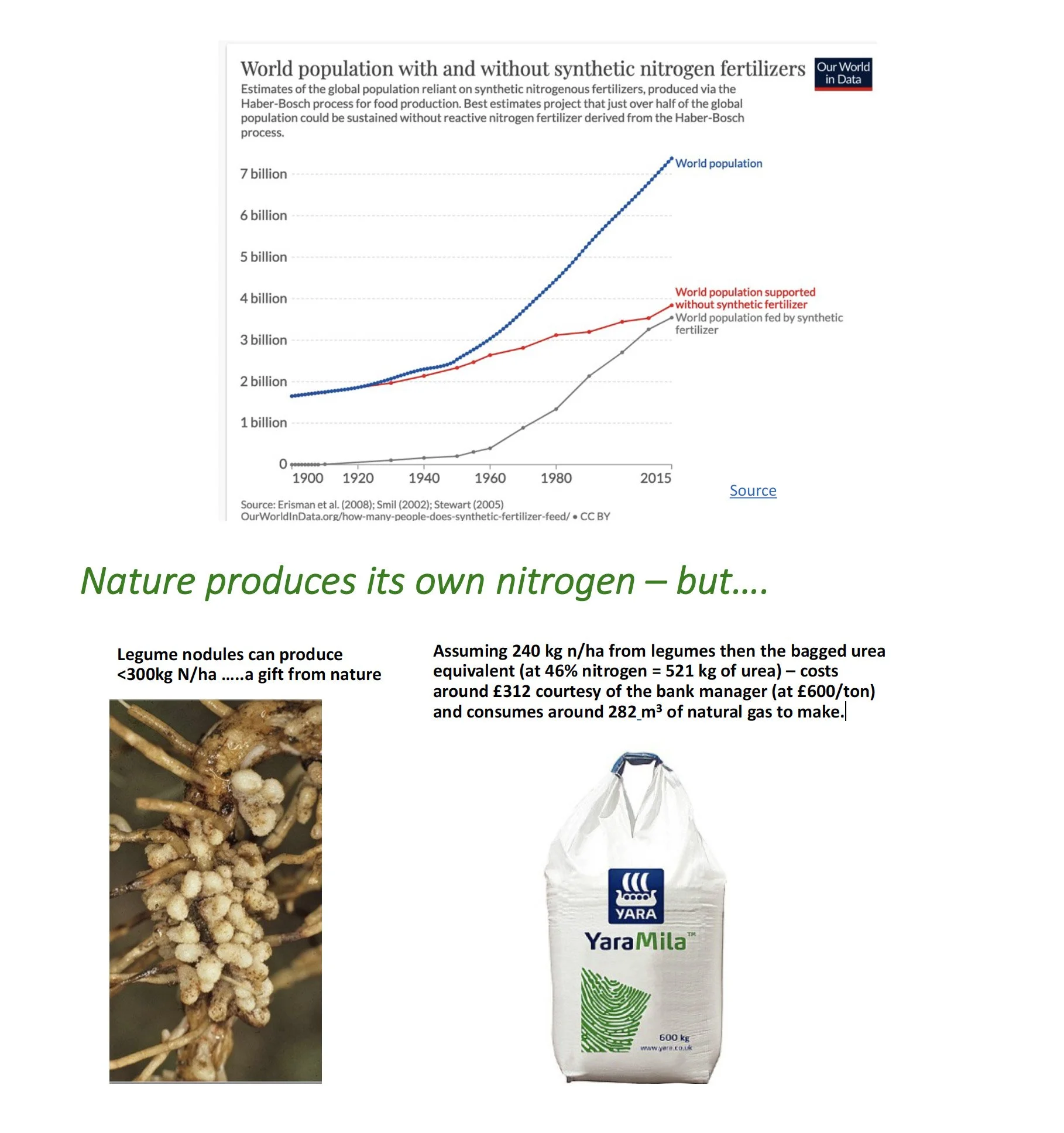

[5] The efficiency of such nutrient use is very low. Artificial N is an inefficient way of feeding plants. Around 2% of world energy is consumed producing N fertilisers. Considering the full chain, on average over 80% of N and 25-75% of phosphate fertilisers consumed, end up lost to the environment, to the air and into water, wasting the energy used to prepare them and causing pollution through emissions of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide (N2O) and ammonia (NH3) to the atmosphere, plus losses into the water system of nitrate (NO3-), phosphate (PO4-) and organic N and P compounds to water. Despite this inefficiency, roughly half the food produced in the world depends upon nitrogen fertiliser despite the fact that nitrogen can be secured through plants, building soil by building a relationship with nature.

A pioneering, regenerative farmer friend writes: This issue of debt resonates with me because I inherited my farm with a lot of debt and know first-hand how crippling it can become until you can break the chain…and avoid getting shackled back into it. On the plus side, many of the farmers whom I learnt the most from are people who have ended up in similar circumstances; staring into the abyss has been the main catalyst for refocusing their farms into profitable, sustainable, regenerative enterprises. I think it was Einstein who maintained that you don’t solve a problem by applying the same solution over and over again!. These rare mentors are the ones we should learn from, with the proviso that they have not bludgeoned their way out of debt leaving victims strewn along the wayside. Nor should we forget the fallout of those who didn’t succeed in reinventing their business…reflected in bankruptcies, family breakups and suicides.

This trend of indebtedness has been growing across the world – but things are changing. Perhaps not surprisingly for those of you acquainted with Sir Albert Howard’s Agricultural Testament, farmers in India are already ahead of the curve. Whilst the much-vaunted Green Revolution undoubtedly resulted in significantly higher yields – it came at a cost. Bred to withstand high volumes of nitrogen fertiliser, the new short-strawed varieties of cereals required large volumes of water, fertiliser and pesticides – all financed by debt. Farmers are by nature risk managers rather than risk takers and the green-revolution debt carried with it not only interest but increased risk. As groundwater levels began to fall the cost of pumping increased, crops began to fail and soil vitality declined. Debts increased, land had to be sold and pressures on farmers increased. Something had to give.

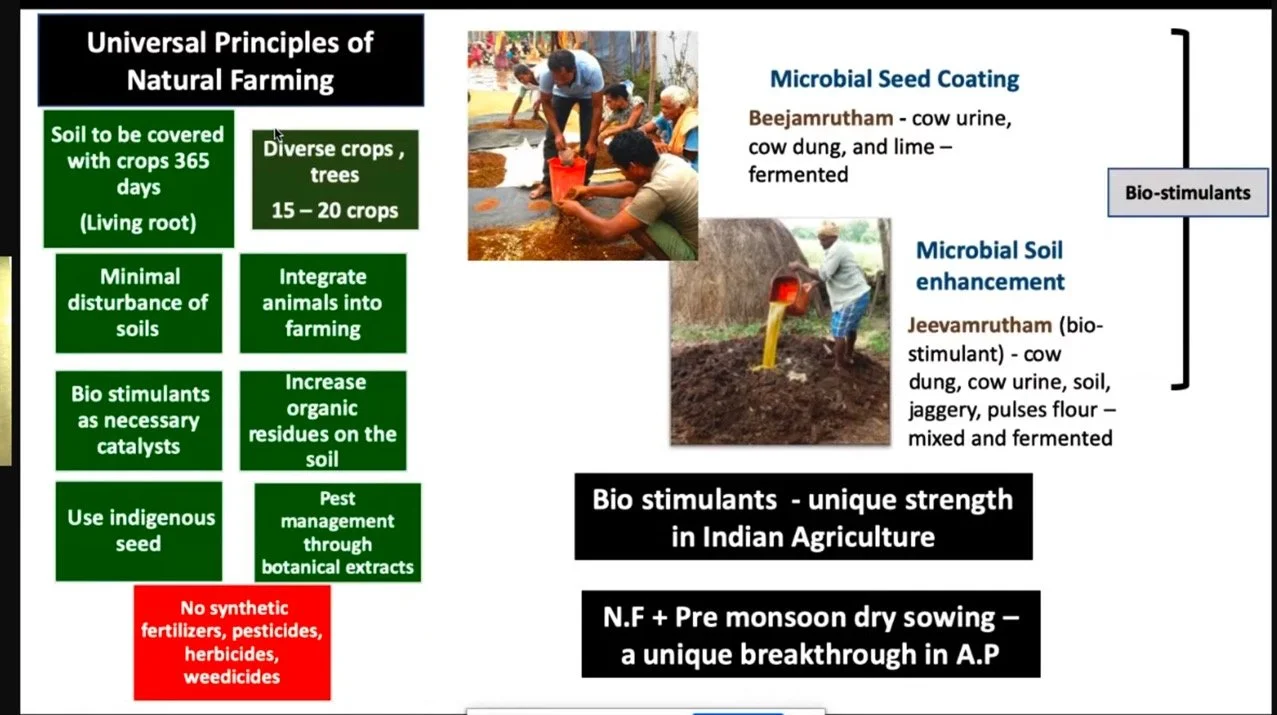

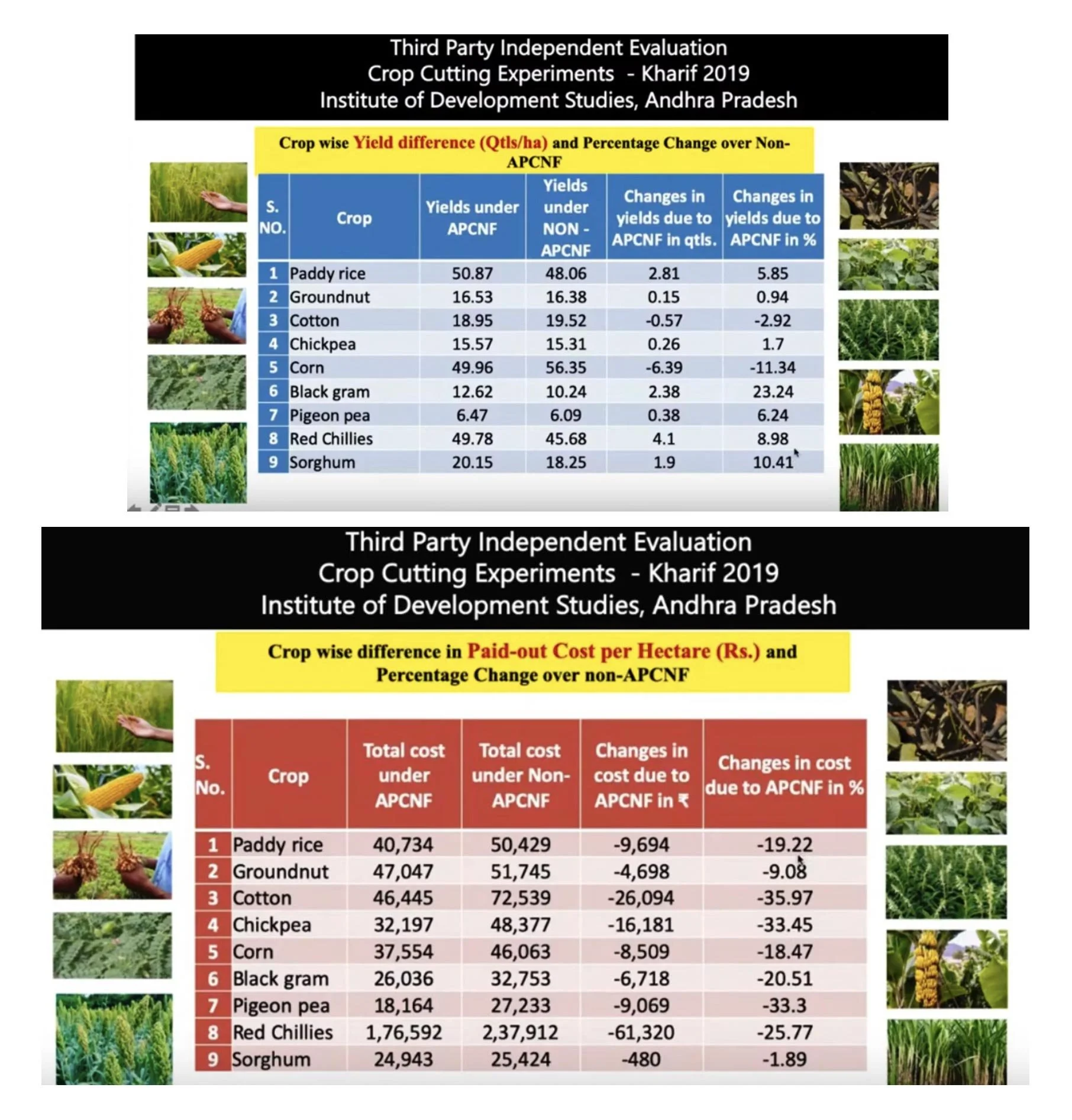

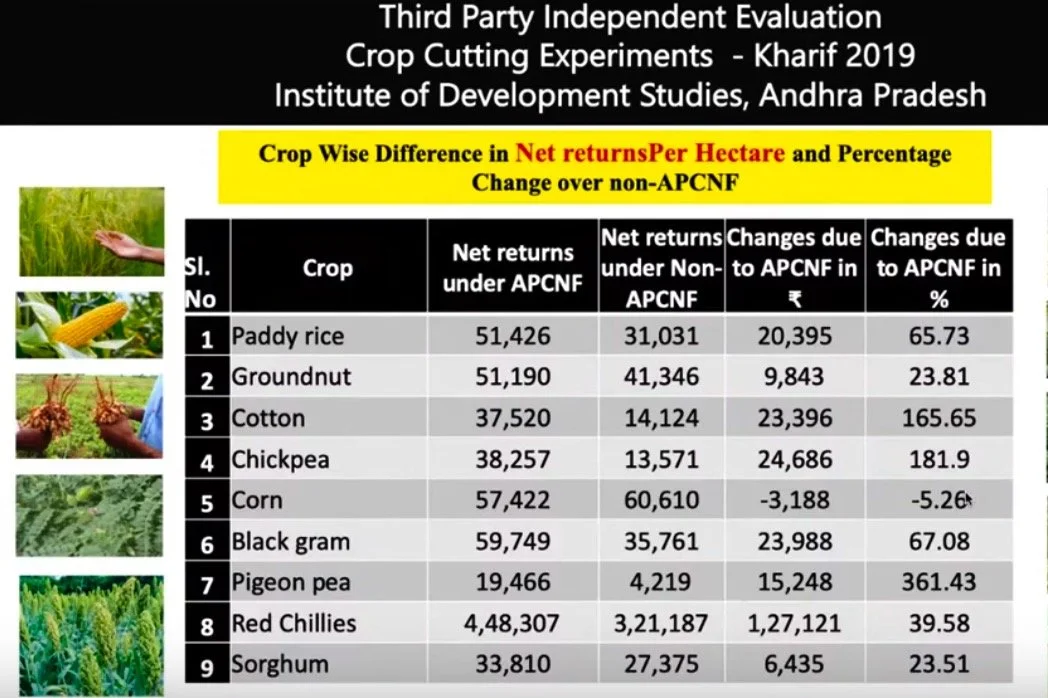

In 2016 the state of Sikkim in Himalayan India became officially organic. Being relatively small it could be considered an outlier. But Andra Pradesh is different. With a population of 50 million and a farmed area of 8.5 million ha (both the same as England), the whole state is in the process of moving to what it calls Zero Budget Natural Farming. This is a method of farming where the need for debt should be zero – using no artificial fertilizers or pesticides. Central to the approach are formulations based on cow dung and urine, locally selected seeds and keeping the soil covered. Independent evaluations show that both yields and net returns have increased, whilst costs have decreased by 10-23%.

Farming on Crutches. In Sierra Leone, I am working with a group of amputees who have established a farm to train other amputees to farm on crutches – without chemicals and without debt. The focus is on becoming indebted to nature rather than indebted to the moneylender.

In the UK, what in the past was sneeringly called “muck and magic” is beginning to become mainstream under terms such as regenerative, agro-ecological and permaculture. Instead of seeking to control nature through the purchase of a range of inputs, a growing number of farmers are seeking to nurture nature to freely share her fruits and reduce the need for debt.

Pasture for Life. In 2010, uneasy with the feeding of grains and pulses to ruminant animals when hunger was common to many of the people with whom I was working, I met two British farmers who were raising their ruminant animals wholly on pasture and we decided to encourage others to do the same. It has morphed into the nationwide Pasture for Life movement – creating a closed loop within the farm, focused on the health of soil, pasture and animal and with little (if any) need for purchased inputs.

Time was when debt and reinvestment remained local and visible, staying in the circular economy where people knew each other, had reputations to protect and so effectively selfpoliced and built the resilience of the community. With big Agri/Pharma the money is sucked out of local economies to large corporates with armies of lobbyists and PR people creating a spiralling circle of indebtedness and servitude. Within the world of farming, this trend away from such crippling debt is not going away. The rising price of energy and fertilisers is already forcing a rethink. India will continue its shift towards natural and debt free farming and other countries will follow suit – with significant implications for the banks and corporates that currently profit from farming. In addition to the many obvious benefits there is another upside to this development. Pouring large amounts of loans into businesses reduces mental acuity – giving renewed credence to the maxim of Sir Ernest Rutherford: ‘We haven’t got the money so we’ve got to think!’

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION