MITIGATING CLIMATE CHANGE IN AFRICAN FARMING

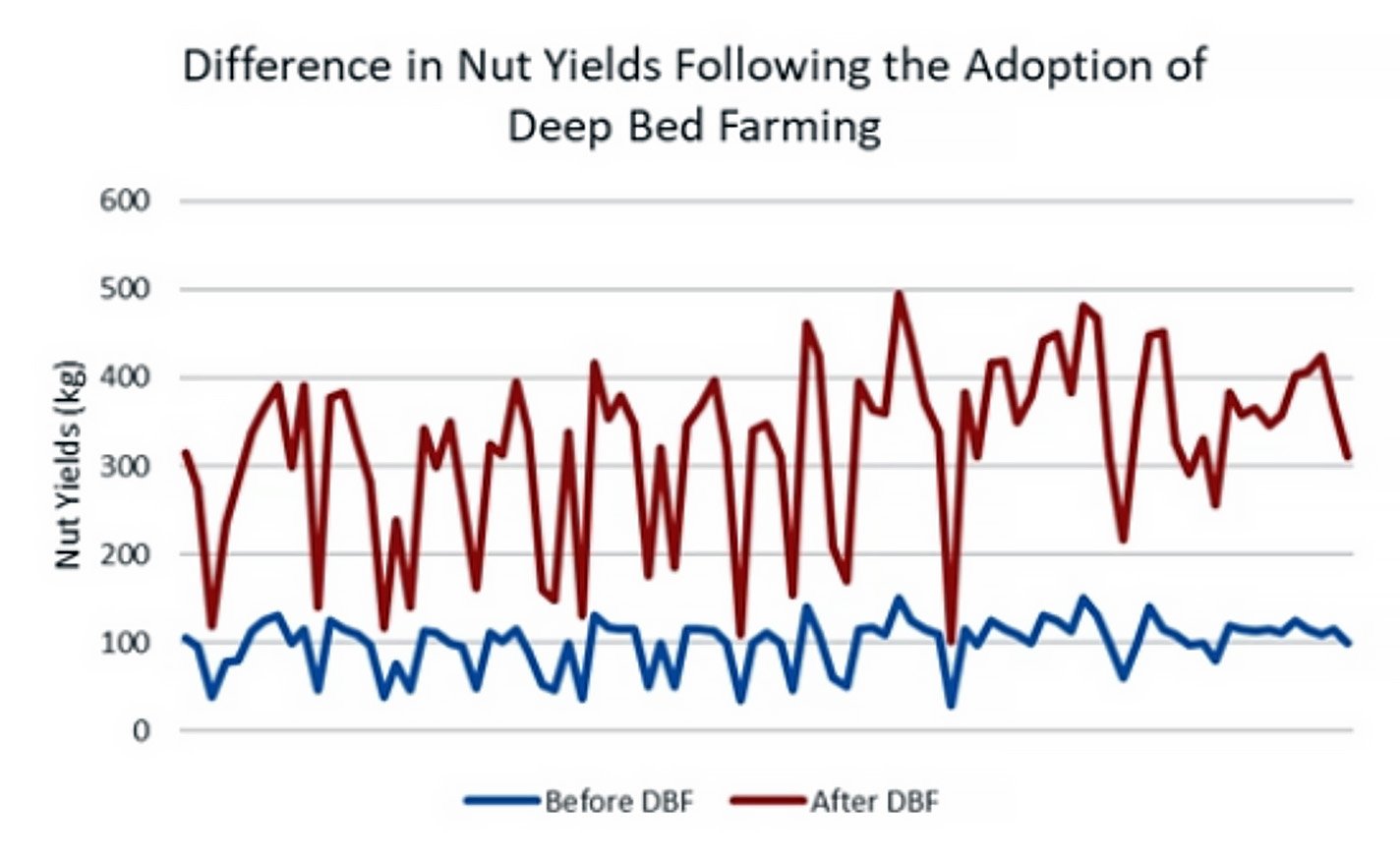

Recently, I attended a meeting of Tropical Agriculture Association International (TAAI) held in memory of the internationally respected soil scientist Francis Shaxson and his pioneering work in Malawi on combating soil erosion. He showed that compaction (a hard pan caused by the constant movement of human feet and the swing of the hoe) was restricting both the free movement of water and the development of roots - resulting in rainwater running off the soil surface and causing heavy erosion. From this work emerged Deep Bed Farming (reflected in the Tiyeni initiative) in which the pan is physically broken up and the land reconfigured with ridges and walkways so that water is retained, soil is conserved, and no-one walks on the land in which the crops are raised. No artificial fertiliser is used. The results are dramatic – see here for peanuts, where there has been a 125% increase in yield.

I have not worked on farming in Malawi, but I did spend a lot of time there between 2010-14 working in the rural areas on water and sanitation. I can remember that at that time, government policy, supported by the World Bank and others, was to increase access to artificial fertiliser – at significant cost in foreign exchange. This was seen as the only way to feed the nation. I can also remember that a large commercial farming company was inviting farmers to give them their cow manure (the value of which they recognised – as does Rothamsted today) in return for bags of artificial fertiliser. The Tiyeni approach shows that both yields and resilience can be increased without the fertiliser, which was previously considered essential.

Moving to Zimbabwe, here you can watch a four-minute clip reflecting on the damaging influence of the corporate world on the small farmer. As you will see from this article, the African Development Bank is endorsing this corporate approach with a massive multi-billion-dollar programme to industrialise African agriculture. An Africa Fertiliser and Soil Health Summit took place in Nairobi from 7th to 9th May 2024, convened by the African Union. Perhaps reflecting that fertiliser comes before soil health in the title, the resulting Nairobi Declaration highlighted the shortfall in fertilizer use in Africa as compared to global averages (18kg/ha vs 135kg/ha) as well as the problem of declining soil health and soil degradation.

A 10 year Fertilizer and Soil Health Action Plan (FSHAP) is proposed, which integrates the programme of the ongoing ‘Soil Initiative for Africa’ (SIA), organised by the Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA) and funded by USAID, the Gates Foundation and others. The FSHAP puts fertiliser, as well as the use of high-yielding (mainly hybrid) crops, at the heart of their approach – not recognising that there are other options that involve working more closely with nature. These initiatives are couched in terms of promoting soil health, but in reality, they reflect a pharmaceutical approach to its health - based around chemicals and forcing the soil rather than nurturing it [1].

A report by the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa notes that “Critics, including the President of Ireland, have voiced concerns over the initiative’s one-size-fits-all approach and its emphasis on large-scale monocropping, formal seed systems, and high-tech solutions such as climate-smart agriculture, digital and precision agriculture and chemical inputs. These methods are argued to be out of reach for small-scale farmers due to their cost, risk to the environment and threat to their autonomy and traditional practices”.

It further notes: At the heart of the controversy is the Dakar II initiative’s tendency towards a one-size-fits-all model of agricultural development — a strategy to agro-industrialise Africa. This approach is heavily reliant on corporate hybrid seed systems, hi-tech solutions, imported inputs, GMOs and large-scale monocropping of maize, rice, and soybeans. As such, it overlooks the rich diversity of needs, cultures and ecosystems across African nations and communities. It not only sidelines small-scale farmers – who are the cornerstone of our continent’s food security and cultural heritage – but poses grave risks to our environmental diversity and indigenous agricultural practices.

For Sierra Leone, the AfDB plan aims to increase milled rice production by at least 25% annually. This will be done by investing in irrigation, mechanization and processing. An additional 100,000 ha will be “put under cultivation” to produce cassava for the purpose of processing into flour and starch.

In 1979 I was asked by the World Bank to comment on an application for a loan from the Sierra Leone Produce Marketing Board (SLPMB) to import tractors so that they could go into the large-scale production of peanuts[1]. As I was in Bamako at the time, I offered to visit the SLPMB and make a preliminary assessment. I spent 10 days travelling round the country, just me and a driver, and concluded that the farmers in the villages were quite capable of producing peanuts themselves, but that they lacked the certainty of a market and a fair price. Out of further work emerged the National Produce Company, whose capital investment consisted only of a few pickup trucks, which offered a secure market to local farmers as well a fair price (which was agreed annually before planting). Success with peanuts led on to a similar approach to the promotion and purchase of rice, ginger and Pentadesma butyracea. The company continued to operate until 1996 ,when the civil war forced its closure. No tractors were imported. There was no large-scale production of peanuts. The need was simply for a secure market at a fair price. The farmers did the rest.

Rory’s Well is a small project in the east of the country on the border with Liberia. Starting with the provision of water, it moved into encouraging a move away from slash and burn to a more sustainable approach to farming and to the successful introduction of beekeeping. Latterly, it has introduced the Inga tree [2], a fast-growing legume whose leaves provide both shade and mulch whilst the bacteria in the root nodules produce nitrogen.

A report on the effect of the tree on yields of maize can be found here. These are not formal replicated trials, but increases in yield exceeding five times have been observed. The picture shows maize being harvested amongst the Inga trees.

Farming on Crutches offers young amputees the opportunity to learn how to farm according to agro-ecological principles – central to which is the making of Bokashi from organic material (both plant material and poultry manure), the fermentation process being facilitated by organisms harvested from nearby forest soils. All chemicals are excluded.

In contrast to this nature-based approach, a word search of the AfDB plan for Sierra Leone reveals no mention of (soil) biology, carbon, organic, ecology or conservation, whilst a search for agro-ecology leads only to agro-chemicals (mentioned 4 times), whilst fertilizer is mentioned 7 times. A recent exchange with a local farmers’ leader highlighted their need for access to tools, working capital, medical facilities, access to land and the capacity to save their own seed. In relation to land, where the AfDB plan is taking land away from farmers, the only option may be for these small farmers to farm upwards through multi-layered farming and forest gardening.

In Malawi the AfDB’s plan is focused on increased production of soybean and rice through establishing agro-industrial parks for value addition; productivity enhancement through mechanization and research/technology development, and rural road infrastructure. A word search reveals that there is no mention of (soil) biology, carbon, organic, ecology, biodiversity, erosion or conservation, whilst fertilizer is mentioned six times.

I mention this because, as is evident in the AfDB plan and in much of academic literature around feeding the world, the focus is on the application of technology rather on nurturing nature - as with the Inga Tree or addressing some of the basic issues that face farmers. To give just one example, an Indian friend started the first microfinance initiative in Bihar some twenty years ago at a time when no-one believed it could work in such an economically-deprived state. As many of his loans were to finance the purchase of a cow, he employed a vet whose job was to routinely meet all the farmers who had such loans and checking on the health of the cow. A significant proportion of the issues concerned fertility. He also invested in a small reverse osmosis plant to produce clean water and distributed it round the villages at cost – winning the appreciation and respect of the communities within which he operated. His approach was to listen, to engage, to understand and to support these communities.

Looking more widely within India, particularly in Andra Pradesh, where there are 6 million farmers on 8.5 million hectares (the same farmed area as England), there is a modal shift at scale away from the intensive methods of the corporation-dominated Green Revolution to what is called Community Managed Natural Farming. CMNF depends on the natural growth of crops without the use of any synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, and with less consumption of ground water. It has dramatically reduced the net cost of production and the few significant inputs used for seed treatments and soil inoculations – cow dung, cow urine, handfuls of soil, jaggery, pulses flour and botanicals for bio pesticides – are all locally available. The policy of the State Government is that the whole initiative its full support of the State Government, with one million farmers having already made the conversion. You will find a report on it here where you will also find that:

Crop diversity is higher - with an average of 4 crops compared to 2.1 previously.

Yields of paddy rice, maize, millet and red gram increased by an average of 11%

Participating farmers saw an average 49% increase in income largely due to a 44% reduction in the cost of inputs.

Labour intensity is 21% higher.

farmers reported 33% fewer sick days and health costs were 26% lower compared to conventional farms.

When encouraging change it is important to listen, learn about and understand what already exists – including its potential to change and what is preventing it from so doing. As far as possible, build on what exists – be it infrastructure, knowledge or relationships. Encourage change through a positive message, through inspiring stories, through providing evidence that making change is worth it and addressing the issues that prevent it happening. This is change from the ground up – as worked so well with the National Produce Company.

In Sierra Leone, a small charity has demonstrated how the introduction of the Inga tree has more than doubled yields, increased water retention and rebuilt community life. Another tiny initiative, Farming on Crutches, has demonstrated how productivity can be increased by making Bokashi through the harvesting of micro-organisms from forest soils. Both have been achieved at minimal cost and no farmer debt. In contrast, the AfDB plan for Sierra Leone “will invest in irrigation, mechanization, and processing. An additional 100,000 ha will be put under cultivation for cassava production for the purpose of processing into flour and starch.”

In Malawi a small charity, building on the work of an internationally respected soil scientist, has developed a method of farming that addresses two of the key constraints (soil compaction and erosion) and, through basic soil conservation measures, has significantly increased yields, water retention and groundwater recharging – all without fertilisers and without the farmers incurring debt. The government of Malawi is sufficiently impressed to have asked the charity to train all its field officers in the technique – but to do so at the charity’s expense. In contrast, the AfDB plan “will establish agro-industrial parks for value addition; productivity enhancement through mechanization and research/technology development and rural road infrastructure”.

In contrast to the farmer- and nature-based initiatives of Tiyeni, Rory’s Well and Farming on Crutches, with the AfDB plan we see change being imposed by an amalgam of the corporate world and governments, funded by a multilateral institution. With a focus on fertilisers, on seeds of “approved” varieties and on agro-chemicals – and with no reference to nature, biodiversity, soil organic matter, the carbon cycle, conservation or ecology- it will increase farmer indebtedness. In total, the AfDB plan envisages putting 25 million ha (257,000 km2) – an area greater than Ghana or Uganda – under “industrial” production.

Sir Albert Howard, who spent 30 years working in India - observing and learning from small farmers and who shared his knowledge with the emerging organic movement in the 1930s - noted that: “The health of soil, plant, animal and man are one and indivisible”. Nowhere do we see this reflected in the AfDB plan. The voices of nature, and of the millions of small farmers who feed Africa, need to be heard.

Work in progress – 27 November 2024

[1] This onslaught on Africa is confirmed by the focus of the 8th Africa Agri Expo 2025 to be held in Kenya in February 2025. Its promotional email reads…. Africa has more than half of the world's farmable land, and the governments in most African countries are prioritising the development of agriculture by implementing Action Plans, Policies and Schemes to foster this growth quickly. However, to tap the agricultural potential of this historic continent – Africa needs cost-effective technologies, solutions & inputs including agro-chemicals, fertilisers, seeds, irrigation, storage, machinery, agri-tech etc - a vast majority of which need to be imported….This has created exceptional business opportunities for international companies to provide good quality and cost-effective products and solutions to the market………… Africa is a land rich in potential, with abundant resources, fertile soil and strong government support for agriculture. The continent is ready to thrive and is actively seeking cost-effective agri-tech solutions that align with what your company offers. The only challenge for you is how to expand in the continent before your competitors do…………..

[2] Peanuts are a surprising crop to find growing in Sierra Leone, as it is generally considered a dryland crop – grown in areas with 0.6+ metres of rain in the growing season, followed by a dry season for ripening and harvesting - as Sierra Leone has an annual rainfall of 2.5-3m! It was introduced into the country by the Portuguese in the C17 and must have adapted to these high rainfall conditions.

[3] More information on the Inga tree can be found through the Inga Foundation and through Rory’s Well.