GROWING THE PEACE – GETTING TREES ONTO FARMS IN SIERRA LEONE

It is December 2000. I have arrived in Sierra Leone where a brutal civil war is showing signs of coming to an end. I am leading a small team of five people [1 ] charged by Clare Short, the then Minister of Overseas Development, to assess how the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) might help the rebuilding of rural life through reconstruction and reconciliation when peace eventually emerges. We have been given just eighteen days to identify the focus of the project and where it should be based. The project must start within three months with an already allocated budget of £5 million.

[1] Consisting of a doctor, a representative of the military, an economist, a logistician and me (an agronomist)

We arrived at Lungi airport, expecting to take the airport bus then cross the lagoon to Freetown by the ancient ferry. But the ferry was not operating. The only other option was to take this helicopter, owned by a Lebanese group and piloted by three Russians. That a similar helicopter had crashed the previous year whilst crossing the bay did not help to build our confidence, nor did seeing the pilots sipping vodka. However, there was no alternative but to enter what was essentially a tin can that could fly. We sat on benches around the side of the hold with our luggage in the middle. There was no Perspex in the windows and as there were not enough headphones to go round the noise was overpowering. When we reached the other side we all took a deep breath and sighed with relief. It reminded me of flying in a military helicopter in Sudan in the early 1970s, when advising the Blue Nile Cotton company, where the “chef” was happily cooking breakfast in front of us on an open primus stove.

Less than two months later I am back in Sierra Leone again to undertake the detailed planning and put the flesh on the bones of the project that we had earlier outlined and whose proposals had been accepted.

We immediately travelled up country – leaving early in the morning. It is dawn. There is a heavy mist. Being a Saturday there is a curfew in place [2] and there is an eerie silence. In front and behind of us are the Land Rovers of the Gurkhas, our military protection.

As we moved out of the city I noticed the many piles of firewood besides the road, awaiting collection to be transported into the capital, whose population had more than quadrupled in size with refugees from the war.

2 Captain Valentin Strasser, the young officer who was in power from 1992-6 following a coup, mandated that on Saturday mornings no civilian vehicle was permitted to move until each street had worked as a community to tidy up all their rubbish and place it at the end the street where it would be picked up by military vehicles for disposal. A siren would sound when all the streets had been cleaned, after which traffic could resume.

As we travelled further into the rural areas we saw more lorries bringing more firewood into the city. By the roadside were yet more piles of wood awaiting collection. This constant flow of lorries carrying fuel wood into Freetown, and the piles of fuel wood along the roadside in the country, highlighted both the insatiable demand for fuel (particularly in Freetown) and the destruction of trees in the countryside.

That rural people are willing to cut down trees for fuel and for building poles is not surprising, since. Whether sold directly or converted into charcoal, it is one of the most readily accessible forms of earning cash. But the felling of these trees nagged at me.

As we neared the town of Port Loko I noticed that a species of tree was in flower. Could this be one of those being cut down for firewood? The local Ministry of Agriculture office was deserted as everyone had been laid off. However, we managed to track down two of the former Ministry staff – one of whom was called Mr. Fomba James – and he confirmed that this flowering tree was one of those used for firewood.

He further explained that most of the wood used for fuel comes from Acacia auriculiformis (otherwise known as the Matchstick Tree) which burns well even when full of sap and leaves behind a valuable and popular charcoal product whilst its dense wood and high energy [3] contribute to its popularity. The resulting charcoal glows well with little smoke and does not spark and is also popular in the villages for smoking fish and cooking. The main source of wood for building poles is a related species (Acacia mangium). Both species are fast growing [4] and regrow from the base of the stump when harvested. Thus informed and enthused we commissioned them immediately to harvest 15 kg of seed (in the ratio 75% fuel wood and 25% building poles) from selected trees – providing them with tools and bags and payment.

3 calorific value of 4500-4900 kcal/kg

4 four years to harvest

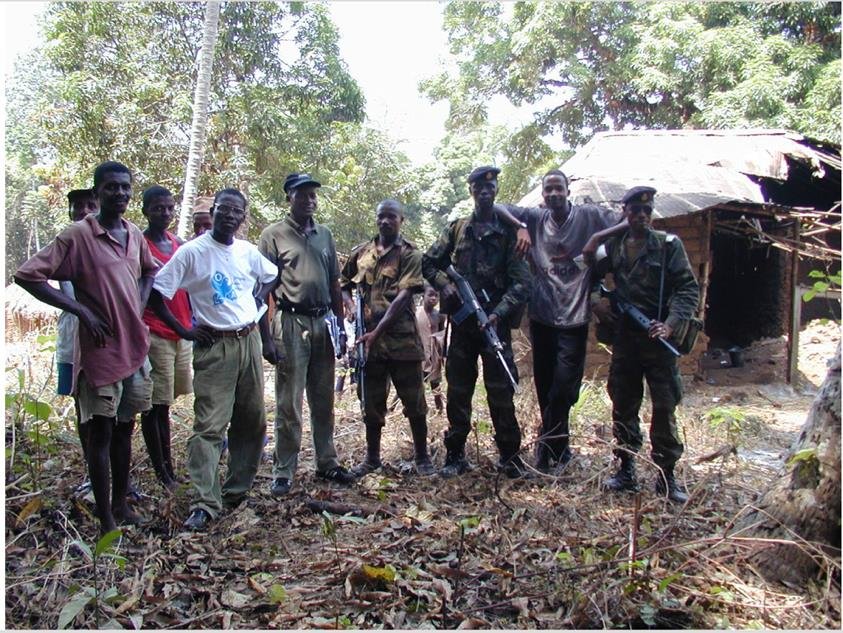

The picture above includes both former Department of Agriculture staff – who collected the seeds (Fomba James is in the white T-shirt) - and those assigned to protect us. Behind the trees is a river. Beyond the river is no man’s land.

Within a few days the seed had been collected and planted out in the near-derelict nurseries - alongside overgrown seedlings of other species (mainly Gmelina and Tectonia.)

We asked Mr James to plan a project to utilize these seedlings. The resulting Community Tree Planting for Sustainable Development Project focused on building up both Ministry-owned and community-owned plantations. It aimed to benefit around 3,000 households and 75 former combatants through providing employment as well as, in the case of community-based projects, a medium-term source of sustainable income.

317,000 seedlings were established [5] for both fuel and building poles. In October, barely eight months later, they were distributed to the farmers for planting out. The project also encouraged the interplanting of the young trees with crops such as sweet potatoes to generate immediate income. Call it serendipity, but by acting on a hunch and seizing the moment we had, by having those seeds collected adjacent to no-man’s land, provided several thousand farmers with a resource that would serve them for years to come.